Issue, No.8 (December 2018)

The challenges of harmonising income data from middle-income countries

There has been tremendous progress in the measurement of inequality and poverty in the developing world, although serious problems of consistency and comparability still remain…

(Alvaredo and Gasparini, 2015)

From its inception in the 1980s, LIS has consistently focused on high-income countries. Then in 2007 a pilot project was carried out with the collaboration of a team at the World Bank in order to study the feasibility of including middle-income countries into the LIS Database. Following the decision to go ahead with this expansion, LIS has made some conceptual adjustments and changes to its list of harmonised variables in order to accommodate more diverse labour market characteristics, social benefit structures, consumption patterns, transnational income flows and within-country variability, and hence maximise its applicability to datasets from both high- and middle-income countries. After ten years of harmonising data from middle-income countries alongside the high-income ones, LIS has acquired considerable expertise with respect to the main challenges which are typically found when working with income micro data from these sources. An overview of all such issues is available in a recent UNU-WIDER working paper by Checchi et al. (2018). Among several caveats discussed in the full version of the paper, this short note mostly focuses on issues concerning the measurement of income.

First and foremost, indicators of inequality, poverty and well-being are still prevalently based on consumption rather than income data, which often implies that income micro data are either non-existent or insufficient for the purpose of calculating robust income indicators (not collected, collected but not provided, collected but not exhaustive enough to capture the totality of household income).

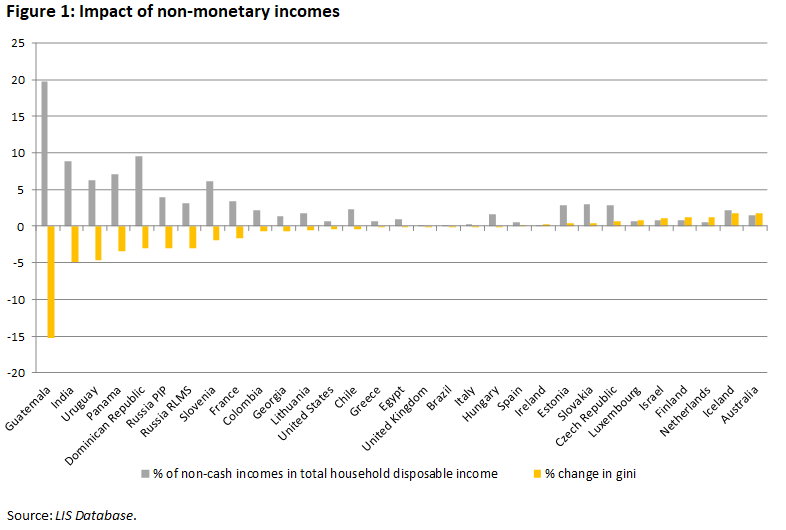

In middle-income countries the proportion of non-monetary incomes from own consumption and social and/or private assistance-based transfers is much more important than in high-income countries, and its effect on inequality and poverty measures can be significant (see Figure 1, where only the LIS countries that collect non-cash incomes are included).

When adjusting the variable list at the time of the inclusion of middle-income countries, LIS adjusted the concept of disposable household income to also include non-monetary incomes. Whereas this adjustment was necessary in order to get a more unbiased picture of the households’ standards of living in those countries, the inclusion of those incomes in the data has often proven to be particularly tricky. The main issues can be summarised as follows:

- The very first problem is due to the fact that coverage of the non-monetary incomes collected by the different surveys differs widely across countries, which has implications for comparability. For example, in surveys that are chiefly focused on consumption, the value of most goods and services consumed but not paid for (either because own-produced or because received from the employer, the government, charitable institutions or other private households) is collected with great detail and precision, whereas in other types of surveys the availability of such goods is much more scarce.

- Another problem arises with the non-monetisation of quantities of goods and services. As of this moment, LIS has taken the approach to only include those incomes that have been monetised by the data provider, thus increasing the potential bias due to the fact that in some countries, for purely practical rather than conceptual reasons, the final income concept includes a greater share of non-monetary types of income than in other cases.

- Somewhat arbitrary assumptions are also made in cases where non-monetary incomes are collected in different sections of the questionnaire (among consumption variables, among the household level incomes from household activities, and among individual level labour incomes). It is clear that these amounts will certainly overlap to some extent and that obtaining a final amount that does not include any under- or over-counting of some of the income sources is proving extremely hard.

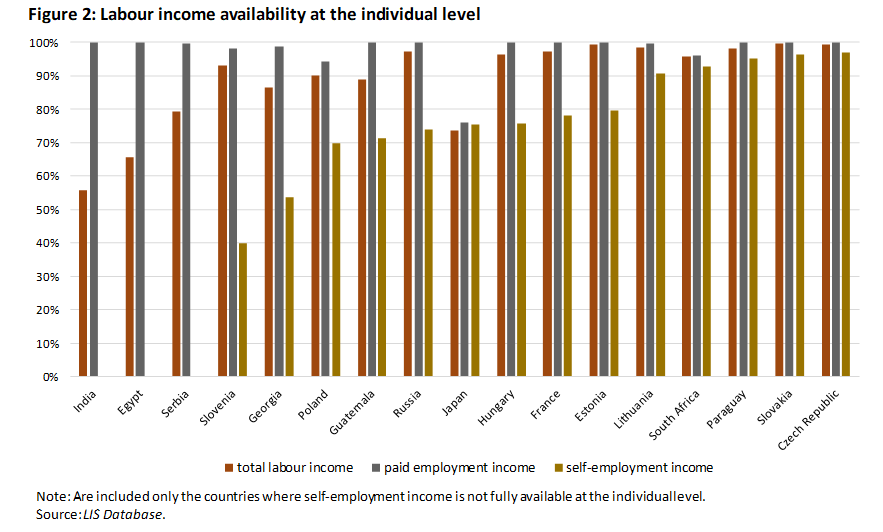

Independently from (but related to) the issue of the non-monetary incomes, another problematic area is that of self-employment incomes in general (see Figure 2 for a cross-country comparison) – especially incomes from farming activities and informal activities. By their very nature these kinds of income are more irregular and difficult to measure, and the reliability of a total household income variable which is made up in large part of those types of income thus becomes much more difficult. In addition, when it is collected at the household level only (as it is often the case in middle-income countries where surveys have specific sections about household activities), the creation of a comprehensive measure of total individual labour income becomes impossible, hence restricting the possibility of using such an important variable in many empirical analyses.

Finally, the treatment of taxes and social security contributions also varies from middle- to high-income countries. The very low reliance on direct taxes in most middle-income countries implies that in many surveys the borderline between gross and net incomes is often unclear. In some surveys incomes are collected partly gross and partly net (often only wage income being gross of taxes and contributions while all others are net); in other cases, it is not clear from the questionnaire or survey methodology whether incomes should be collected gross or net of income taxes and contributions. Such imprecision unavoidably leads to mixed results as regards data collection. Moreover, several middle-income countries provide income data only in gross terms, without any indication of the amount of taxes and contributions paid on them. One implication of this is that in order to obtain a measure of disposable income comparable to other countries taxes and contributions need to be simulated. In any case, even in the presence of full information on taxes and contributions, the low reliance on direct taxes relative to the indirect ones in middle-income countries might add a bias to the comparability of well-being indicators based on disposable household income. If indirect taxes were also taken into account, the true difference in inequality between high- and middle-income countries might even be more exacerbated than what the figures show.

In conclusion, in spite of the manifold efforts at the various levels of the data production chain (survey conception, implementation, data editing and data harmonisation), too many significant gaps remain to ensure proper consistency of income micro-datasets from high- and middle-income countries. The question of whether those two sets of data can be analysed within the same framework, or should be kept separated, therefore remains an important one. LIS has adopted the view that a common framework is possible while at the same time strongly emphasising the importance of highlighting all the caveats that go with such an approach. A next step would thus be to analyse the potential biases due to those challenges.

References

| Alvaredo, F., and L. Gasparini (2015). Recent trends in inequality and poverty in developing countries. In Handbook of Income Distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 697-805). Elsevier. |

| Checchi, D., A. Cupak, T. Munzi and J. Gornick (2018). Empirical challenges comparing inequality across countries: The case of middle-income countries from the LIS Database. WIDER Working Paper 2018/149. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER, accessible here. |