Issue, No.5 (March 2018)

The long term evolution of inequality of opportunity1

The recent empirical literature on Equality of opportunity (EOp) has provided a significant body of cross-country comparative evidence on inequality of opportunity. See Brunori et al. (2015) for a first assessment of the existing evidence and Ferreira and Peragine (2016), Ramos and Van de Gaer (2016) and Roemer and Trannoy (2015) for methodological and conceptual issues related to the measurement of EOp.

A common feature of the existing literature is the static approach: most of the empirical analyses use a snapshot income distribution as the relevant distribution of individual advantages, and is limited to computation of inequality of opportunity in a given point in time for a given country or set of countries.

Much less evidence is available on the evolution over time of the inequality of opportunity, due to data limitations. Even when repeated cross-sections are available for the same country, there are three different ways one can analyse the evolution of inequality of opportunity, which correspond to three different concepts of inequality dynamics: (i) inequality measured across repeated snapshots of the population (repeated cross-sectional analysis); (ii) inequality measured along the life course (longitudinal analysis); (iii) inequality measured across generations (cohort analysis).

While analysis (ii) requires the availability of a rich longitudinal dataset containing information of individual incomes and circumstances over the entire life cycle of the individuals, analyses (i) and (iii) can be potentially carried out by using repeated cross section surveys, hence are much less data demanding. Aaberge et al. (2011) provide a good example for an analysis of long term inequality of opportunity along the lines of concept (ii). And a recent paper (Bussolo et al. 2018), which is the basis for this brief, focuses on analyses (i) and (iii). In addition to a description of the evolution of inequality of opportunity, this paper exploits the time variation of EOp to study its main determinants. By doing so, we move the research on EOp a step forward by proposing and testing a (simple) empirical model that accounts for the contributions of these determinants to the change over time of the inequality of opportunity (for the technical details please see Bussolo et al. (2018).

The definition of inequality of opportunity is provided by the distinction, among the factors influencing the individual achievements, between individual efforts and pre-determined circumstances – defined as those which lie outside the realm of individual responsibility. The EOp approach considers that inequality due to the former is not ethically offensive, whereas it suggests that differences in individual outcome due to the latter represent a violation of the principle of equality of opportunity and should thus be remedied. The decomposition analysis indicates that, other things constant, EOp increases when:

- there is a reduction in the intergenerational persistence of education.

- there is a reduction in the (private) return to education.

- there is a reduction in the effect of family network in the labour market.

- there is an increase in the variance and covariance of the non-observable components.

- there is a reduction in the variance of the educational attainment of the previous generation.

Inequality of opportunity can trend downward if the channels of intergenerational persistence become less important. As it is intuitive, if the educational investment becomes irrelevant (because education yields insignificant returns in the labour market), then parents become unable to transmit privileges to the off-spring, and inequality declines as a consequence. Similarly, if parents are unable to actively networking on behalf of their children, the disadvantage due to circumstances will decline.

The LIS: Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg is the main data source for our analysis, which covers four countries (Italy, Germany, France and Switzerland), while the data for fifth country United Kingdom was obtained from accessing the original provider.

Our selection rules include individuals aged 25-80 with a positive personal disposable income, harmonised across the surveys within and between countries. Wages, self-employment income, and pensions which were available in all surveys at the individual level were considered as genuine individual incomes. Other less clearly person-related income sources were reallocated equally to both the head and the spouse to maintain consistency over time, as collection varied across the surveys and countries. Incomes are converted to constant prices using the national consumer price index. Parental education is typically a categorical variable recording the highest educational attainment in the parental couple. In order to estimate a unique coefficient associated to the intergenerational transmission of education, we have converted them into years of education.

Using these data, we have estimated total inequality, absolute inequality of opportunity (namely inequality computed over incomes predicted according to circumstances) and relative inequality of opportunity, first on the country-survey level and then further disaggregated by age and birth cohort. For the latter we have partitioned birth years and ages in 5-year intervals and we have retained only cells gathering at least 400 individuals. In order to summarise the information contained in each of the cells, we followed Deaton (1997) and regressed the obtained measures onto age, cohort and survey dummies, and then plotted the results using a smoothing procedure (LOWESS command in Stata).

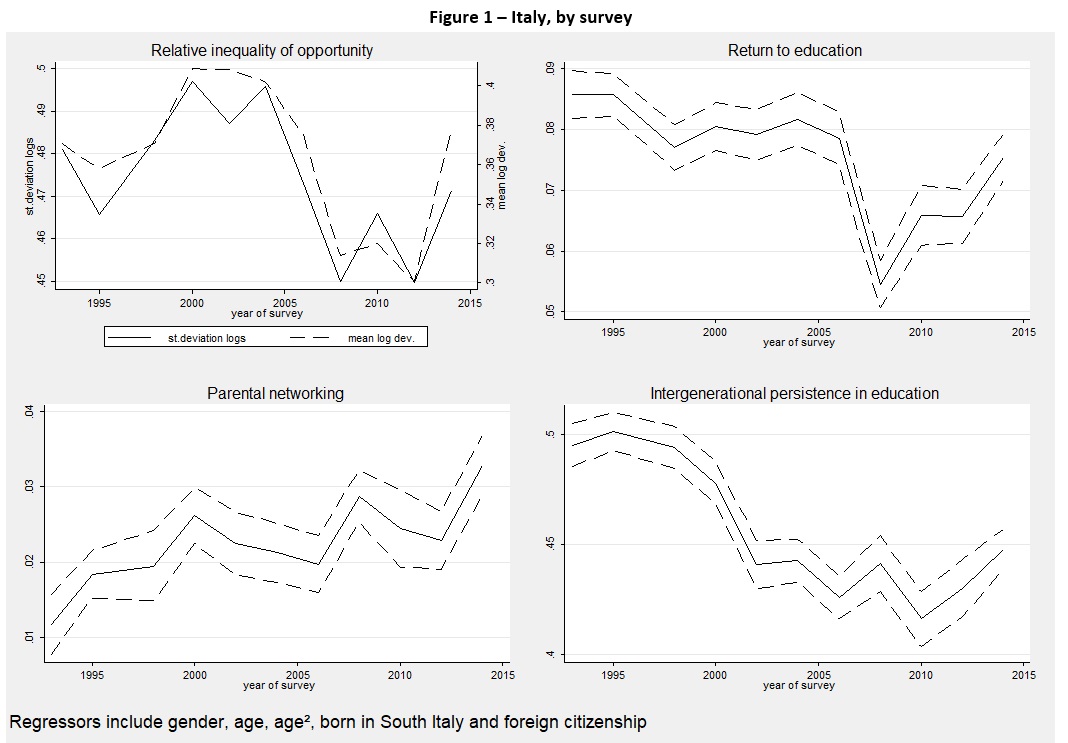

This brief focuses on the results for Italy, results for the other countries are available in Bussolo et al. (2018). Figures 1 and 2 for the Italian data highlight the following. Starting with relative IOp, the analysis by survey shows a clear reduction in relative IOp at the beginning of the 2000’s and then an upward trend starting from the beginning of the 2010. In sum, a rather constant time trend: the value of relative IOp (namely the share of inequality attributable to circumstances) is the same at the start and at the end of the period, also confirmed by the mean log deviation (MLD). As for the magnitude, it varies between 45% and 50% according to the standard deviation of logs and between 30% and 40% according to MLD (see Figure 1).

The intergenerational persistence of education shows a clear declining trend, with some signs of a reversal in recent years. The reduction can be linked to the expansion of education that took place in Italy following the compulsory education reform at the beginning of the 60’s. In connection to the increasing supply of education, the returns to education, at least until the late 2000s, have also been trending downwards. Given these trends, the question becomes of why the inequality of opportunity in income has not also been declining. The answer is that the increasing trend of parental networking has been a counterbalancing force.

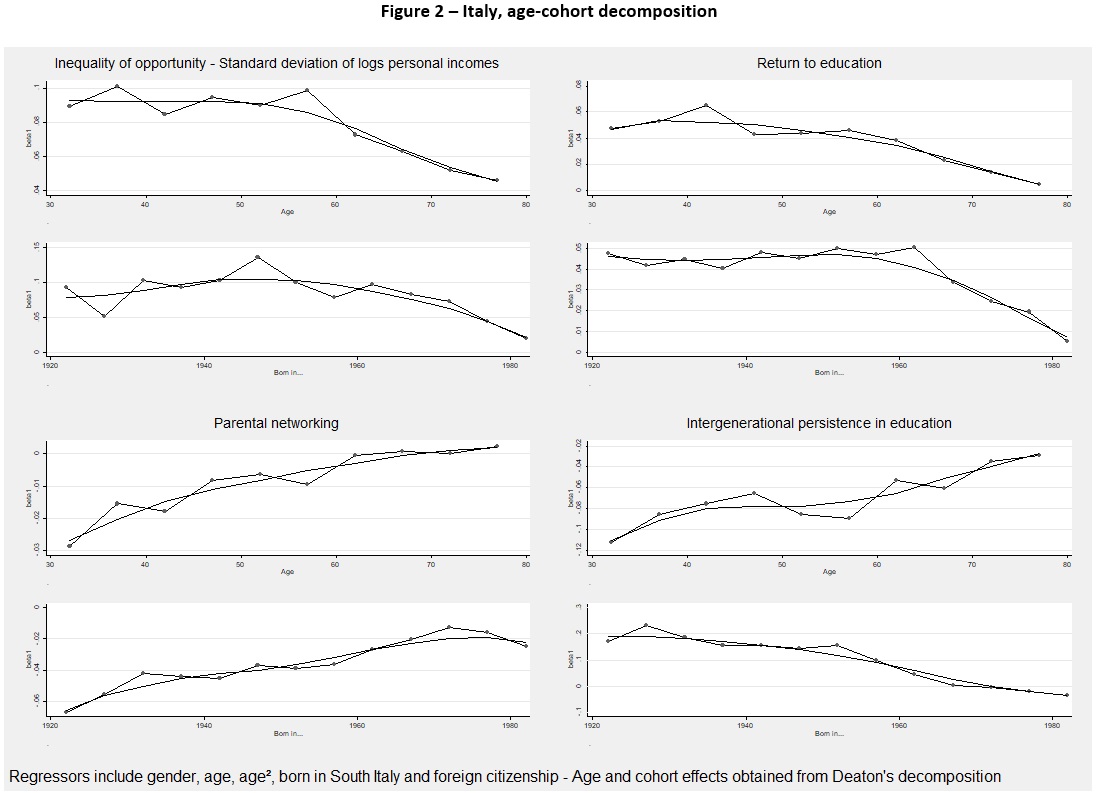

This answer is largely confirmed when looking at both the age and the cohort analyses, which also shows some additional interesting facts (see Figure 2).

Cohorts born more recently vis-à-vis cohorts born in the past, irrespective of at what age one looks at them, are characterized by a lower return to education and a lower intergenerational persistence of education, but also by a higher level of parental networking. In sum younger cohorts experience a slightly lower, but by not much, inequality of opportunity than older cohorts, but for different reasons.

In addition, one can see – for all cohorts – an inverted U shape for the age effect of the inequality of opportunity in incomes. This means that inequality of opportunity tends to be low for younger individuals, then it increases, and finally towards the latter part of the life cycle, circumstances becomes less important and inequality of opportunity for incomes amongst older individuals is lower.

Inequality of opportunity – what we have learned

By replicating this decomposition for all the countries in our sample, it is possible to highlight the following stylised facts:

i) In all the countries and the period considered, inequality of opportunity represents an important portion of total income inequality, with values ranging from 30% to 50% when inequality id measured by standard deviation of logs (and reaching a lower share in case of adopting the mean log deviation).

ii) In general, inequality of opportunity shows a stable or declining pattern over the period considered in all countries.

iii) On the other hand, in all countries considered, there has been a clear enhancement of equality of educational opportunities (as captured by the reduction of intergenerational education persistence).

iv) In some countries the egalitarian process taking place in the education system and the reduced skill-premium in earnings has failed to translate into decreasing opportunity inequality in the space of income because of the increasing role of parental networking. This mechanism seems to be at work notably in Italy.

v) In some other countries (France, Germany and Great Britain), where both returns to education and the family networking followed a more constant pattern, inequality of opportunity seems to decrease both in the education and in the income sphere.

Decomposing of inequality of opportunity trends according to the age and cohort effects, allows to identify the following additional facts:

vi) In all countries considered, inequality of opportunity decreases with age: the effect of circumstances at birth seem to weaken over the life cycle. This pattern marks a difference of inequality of opportunity with respect to what is generally found for income or consumption inequalities, which generally follow an increasing path.

vii) The decreasing pattern of relative inequality of opportunity in France and Italy is associated with a consistent declining trend in the return to education and a clear increasing trend in both intergenerational persistence and parental networking. Great Britain shows an increase in the intergenerational education persistence, while Germany is characterised by a stable trend of intergenerational education persistence.

viii) The cohort analysis, on the other hand, shows a more mixed picture: while for Great Britain and Germany the data show a declining path in the values of inequality of opportunity, with younger generation experiencing a lower IOp levels, both Italy and France are characterised by an inverted U-shape pattern.

ix) These trends are associated, in Germany and Great Britain, with a stable or weakly increasing trend of the intergenerational educational persistence, while in Italy and France with a clear declining trend in the intergenerational persistence of education, which is explained by the expansion in education level that has taken place during the last decades.

1 This brief is based on LIS Working Paper 730, Bussolo et al. (2018) – the working paper serves as background paper for the World Bank Regional Report on “Distributional tensions and the sustainability of the social contract in Europe and Central Asia”.

References

| Aaberge, R.; Mogstad, M.; Peragine, V. (2011). Measuring Long-term Inequality of Opportunity, Journal of Public Economics, 95(3-4), 193-204. |

| Bussolo, M.; Checchi, D.; Peragine, V. (2018). The long term evolution of inequality of opportunity, LIS Working Paper Series, No. 730. |

| Deaton, A. (1997). “The analysis of household survey. A microeconometric approach to development policy” Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore and London). |

| Ferreira, F.H.G. and Peragine, V. (2016). Individual responsibility and equality of opportunity, in M. Adler and M. Fleurbaey (eds.), Handbook of Well Being and Public Policy, Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| Ramos, X. and Van de Gaer, D. (2016). Approaches to inequality of opportunity: Principles, measures and evidence, Journal of Economic Surveys, 30(5), 855-883. |

| Roemer, J.E. and Trannoy, A. (2015). Equality of opportunity, in A.B. Atkinson and F. Bourguignon (eds). Handbook of Income Distribution, vol.2B, Amsterdam: North Holland. |