Issue, No.36 (December 2025)

Behind Closed Doors: Intra-Couple Pension and Wealth Gaps in Germany and Beyond 1, 2

Key Messages

- Significant pension and wealth gaps persist within retired couples, particularly in West Germany, where gendered employment trajectories translate into markedly lower individual resources for women.

- Institutional design matters: countries with dual-earner employment models and more universal public pensions show much smaller intra-couple disparities than systems relying heavily on earnings-related and private pension pillars.

- Strengthening individual pension rights and supporting continuous employment for women—through childcare provision, equitable parental leave, and inclusive pension rules—is essential to ensuring financial security for both partners in retirement.

Introduction

Financial security in retirement is increasingly shaped by the opportunities and constraints individuals face across their working lives. As pension systems in many OECD countries have moved towards greater reliance on individual contributions and private savings, continuous employment and stable earnings have become more important for determining economic stability in old age (Ebbinghaus, 2015). These dynamics interact with strongly gendered patterns of labour market participation, caregiving responsibilities, and earnings trajectories (Madero-Cabib & Fasang, 2016).

Although retirement is often analysed at the individual or household level, it is, for most people, experienced within a couple. Understanding how economic resources are composed and organised within households is therefore essential. The common assumption that couples pool and share their economic resources does not reflect the reality of how pensions and personal wealth are held or managed within a substantial share of couples (see Kapelle (2025) for an overview). This has important implications for autonomy and financial security in later life (LeBaron-Black et al., 2024), particularly for women, who frequently experience longer periods of widowhood and may rely heavily on their own pension entitlements and personal wealth.

Within this broader context, understanding intra-couple financial inequalities is a necessary foundation for analysing gender differences in retirement outcomes and for assessing the effectiveness of pension policies in promoting financial security.

Why Intra-Couple Inequalities Matter

The distribution of financial resources within couples is shaped by institutional structures, tax and pension rules, and the organisation of paid and unpaid work (Kapelle, 2025). Pension systems that place a strong weight on individual contributions can amplify differences that accumulate over the life course (OECD, 2021), particularly when women’s employment trajectories remain more fragmented than men’s (Madero-Cabib & Fasang, 2016). At the same time, focusing solely on household-level aggregates conceals how individuals within couples may enter retirement with very different levels of personal financial security.

Exploring these dynamics helps clarify how current pension arrangements interact with gendered life-course patterns and how vulnerabilities may emerge at key transitions such as widowhood, separation, or the onset of care needs. It also sheds light on how institutional contexts may mitigate or reinforce inequalities that originate earlier in life.

Gendered Accumulation Paths of Pensions and Wealth

Pensions and personal wealth follow distinct accumulation logics. Pension entitlements are generally tied to labour market participation, contribution histories, and the design of public and private schemes (OECD, 2021). These mechanisms reflect the gendered organisation of work and care, as well as the incentives embedded in national policy frameworks. Wealth, by contrast, depends not only on earnings capacity but also on savings opportunities, homeownership, asset markets, and intergenerational transfers (Spilerman, 2000). Some assets are jointly held within couples, while others remain individual. These differences mean that pension entitlements and net wealth may follow different trajectories and respond differently to institutional and life-course factors.

Understanding how these accumulation processes interact within couples provides important insights into the resources individuals bring into retirement and the extent to which inequalities may persist across different forms of economic resources.

Institutional Background: The Example of Eastern and Western Germany

The German case illustrates how institutional legacies continue to shape couples’ financial resources in retirement. Before unification, West Germany followed a male-breadwinner model, with pension entitlements strongly tied to full-time, continuous employment. This framework encouraged gender-specialised roles and resulted in distinct employment biographies for women and men. In contrast, the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) in East Germany promoted universal full-time employment and provided an extensive childcare infrastructure, facilitating more continuous employment among women. These differing institutional legacies shaped the employment histories of today’s retiree cohorts and form an important backdrop for understanding variation in couples’ financial resources in later life.

Using data from the 2017 wave of the German Socio-Economic Panel, we analyse pension wealth—the discounted value of public and occupational pensions over individuals’ remaining life expectancy—and personal net wealth, defined as individually owned assets minus liabilities, with jointly held items allocated by reported shares. The results reveal marked gendered inequalities within couples, which differ substantially between Eastern and Western Germany.

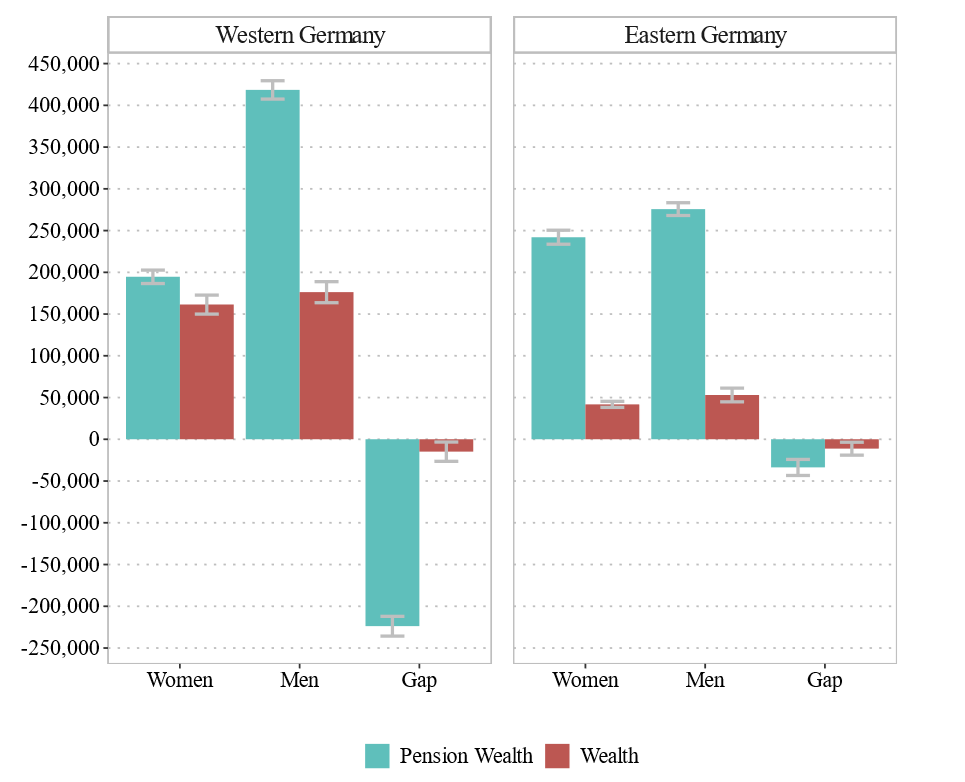

Figure 1 presents the average values held by women and men, along with the absolute differences within couples.

Pension wealth shows the most pronounced differences. In Western Germany, women hold on average €194,600 in pension wealth—about 53% less than their male spouses. These wide gaps reflect the long-term imprint of a labour market organised around the male-breadwinner model, with many women spending extended periods in part-time work or outside paid employment.

In Eastern Germany, by contrast, women’s pension wealth is only around 12% lower than men’s. The much smaller gap reflects the legacy of continuous full-time employment under the GDR, combined with comparatively lower average male pensions. As a result, intra-couple pension differences are more muted.

Gaps in personal net wealth are notably smaller. In Western Germany, women hold around €161,000, about 8% less than men. The narrower difference reflects widespread joint ownership of major assets, especially housing.

Figure 1 Spouses’ mean personal pension wealth and personal net wealth in Euros in Eastern and Western Germany

Source: Own estimations based on data from the Socio-Economic Panel Survey v37. Weighted and imputed data.

In Eastern Germany, overall wealth levels are much lower due to historical constraints on private wealth accumulation. Women hold on average €41,800, with an absolute intra-couple gap of roughly €11,200, amounting to a 21% relative difference. Although the percentage gap is larger than in the West, the underlying absolute wealth differences are considerably smaller.

Across both regions, a significant share of couples report similar levels of personal wealth—around 42% in the Eastern and 30% in the Western—which is largely driven by joint ownership of housing assets. Financial wealth, by contrast, tends to be more unequally distributed.

Overall, the German case shows that institutional legacies shape intra-couple inequalities long before retirement begins. Pension wealth closely mirrors gendered employment trajectories rooted in West Germany’s breadwinner arrangements and East Germany’s dual-earner model. Personal wealth, by contrast, is shaped more by household-level ownership practices and norms of financial jointness. Regression analyses confirm that pension wealth gaps remain sizeable even after accounting for demographic and partnership characteristics, while personal wealth differences are only weakly explained by such factors.

Pension Differentials in Comparative Perspective

A comparative perspective helps situate the German results within a broader institutional context. Because comparable individual-level wealth data remain scarce internationally, we focus on intra-couple gaps in annual pension income from all sources—public, occupational, and private—using the 2021 wave of the Luxembourg Income Study. The selected countries and contexts—Western Germany, Eastern Germany, Denmark, Luxembourg, Sweden, and the United Kingdom—illustrate different combinations of labour-market arrangements and pension-system designs that shape how men and women accumulate resources across their working lives and into retirement.

These countries and contexts also differ in the extent to which they support gender-equal versus gender-specialised employment patterns. In Western Germany, Luxembourg, and the United Kingdom, couples have historically followed more asymmetric employment constellations, with men typically working full-time and women more often experiencing part-time work or career interruptions. In contrast, Eastern Germany, Denmark, and Sweden are rooted in more egalitarian dual-earner models.

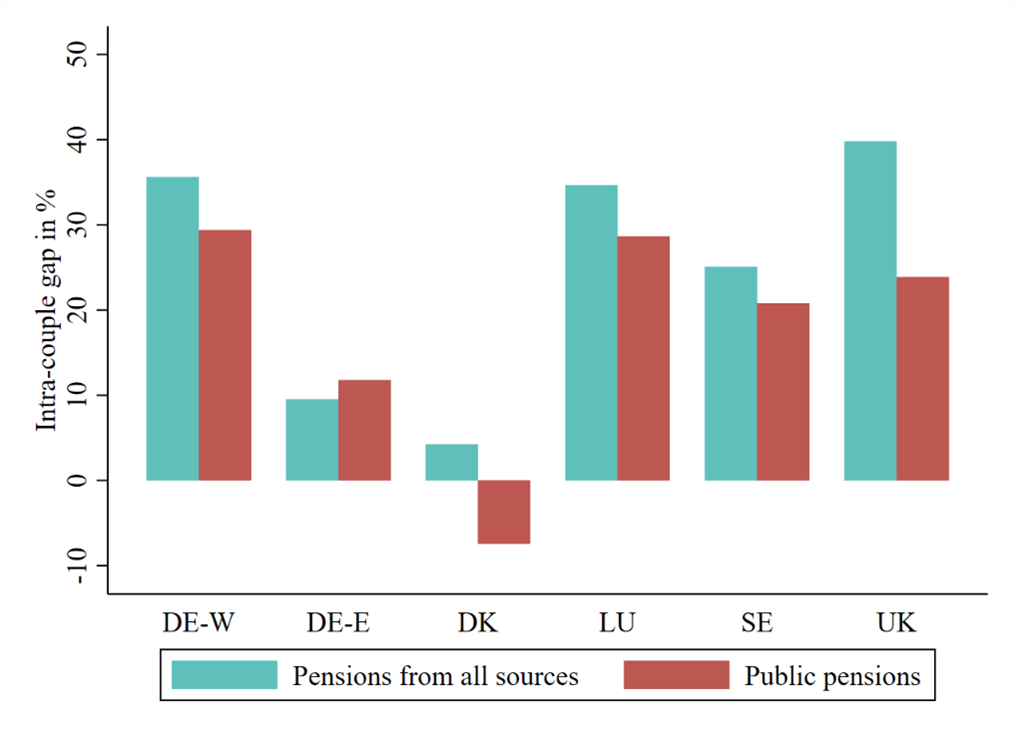

Figure 2 Intra-couple gaps in total and public pensions (annual) across selected countries

Notes: Married and cohabitating partners both at least 65 years old and indicating a total individual pension income >0€. Adjusted for 2017 PPP and weighted.

Source: Luxembourg Income Study 2021 wave

Pension institutions reinforce these patterns in different ways. Bismarck-type systems—as seen in Eastern and Western Germany and Luxembourg—centre on earnings-related public pensions that primarily aim to maintain living standards. Beveridge-type systems, represented here by Denmark and the United Kingdom, rely more strongly on flat-rate or means-tested public benefits focused on income security, with occupational and private schemes generating additional stratification. Sweden occupies an intermediate position, combining basic pensions for older cohorts with increasingly earnings-related and means-tested elements for younger ones.

Figure 2 summarises the intra-couple gaps in total annual pension income as well as in public pensions alone. Considering total pensions, the United Kingdom shows the largest gap between partners at 39.8%, followed by Western Germany (35.6%), Luxembourg (34.7%), and Sweden (25.1%). In contrast, gaps are markedly smaller in Eastern Germany (9.5%) and Denmark (4.2%), consistent with their dual-earner profiles and more redistributive public pension components.

For public pensions, gaps are smaller in most countries, highlighting the role of occupational and private pensions in shaping overall disparities. Public pension differences are highest in Western Germany (29.4%) and Luxembourg (28.6%), reflecting their strong reliance on earnings-related social insurance. Denmark again stands out, with a 7.4% gap in favour of women: while its basic pension provides broadly similar entitlements for both partners, women are somewhat more likely to qualify for income-tested supplements.

Taken together, the comparative findings show that countries combining dual-earner employment patterns with universal or redistributive public pensions tend to exhibit smaller intra-couple gaps. When pension systems depend strongly on individual earnings and private or occupational schemes, differences in women’s and men’s employment histories show up more sharply in their retirement incomes.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

The results from Germany and the comparative analysis make clear that financial resources in retirement are not distributed equally within couples, and that these inequalities reflect both gendered life-course trajectories and the design of institutional systems, most notably the pension systems. Pension wealth and income, in particular, carry the imprint of earlier employment patterns, leaving women with lower individual entitlements even when households appear financially secure at the aggregate level. These disparities matter not only for women’s economic autonomy, but also for couples’ joint resilience: when pension systems reward continuous full-time employment, shocks experienced by the main earner can translate into long-term vulnerability for both partners.

The cross-country comparison additionally shows that these outcomes are strongly shaped by institutional choices. Countries that support stable dual-earner employment and provide a substantial, universal foundation of public pension rights tend to display much smaller intra-couple gaps. In systems where pensions are more tightly linked to individual earnings and supplemented by occupational and private schemes, inequalities accumulated during working life resurface more sharply in retirement.

Reducing these disparities requires interventions at different stages of the life course. On the labour-market side, policies that strengthen women’s continuous and full-time employment—through accessible childcare, flexible working arrangements, and parental-leave schemes designed to encourage fathers’ participation—can mitigate gaps before they emerge. Within pension systems, more inclusive benefit structures can help safeguard individual security, for example, through better recognition of part-time and care-related employment, broader access to occupational pensions, more generous minimum or basic pensions, or instruments such as pension splitting.

A sustainable approach to retirement security recognises that couples share their lives, but not always their economic resources—making individual rights essential. Policies that promote more equal employment opportunities and more balanced pension entitlements and accumulation of other economic resources can help ensure that both partners enter retirement on a more equal and secure footing, benefiting not only individuals but also the long-term fairness and stability of pension systems.

1 This Policy Brief is partially based on the following publication: Kapelle, N., & Weiland, A. P. (2025). Intra-couple gaps in retirees’ financial resources: Their extent and predictors across Eastern and Western Germany. European Societies, 27(2), 288–319. https://doi.org/10.1162/euso_a_00013

2 This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

References

| Ebbinghaus, B. (2015). The privatization and marketization of pensions in Europe: A double transformation facing the crisis. European Policy Analysis, 1(1), 56-73. https://doi.org/10.18278/epa.1.1.5 |

| Kapelle, N. (2025). Money, work, and wealth in partnerships. In D. Mortelmans, L. Bernardi, & B. Perelli-Harris (Eds.), Research Handbook on Partnering across the Life Course (pp. 251-267). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. |

| LeBaron-Black, A. B., Dew, J. P., Wilmarth, M. J., Holmes, E. K., Serido, J., Yorgason, J. B., & James, S. (2024). Pennies and power: finances, relational power, and marital outcomes. Family Relations, 73(3), 1686-1705. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12989 |

| Madero-Cabib, I., & Fasang, A. E. (2016). Gendered work–family life courses and financial well-being in retirement. Advances in Life Course Research, 27, 43-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2015.11.003 |

| OECD. (2021). Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. |

| Spilerman, S. (2000). Wealth and stratification processes. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 497-524. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.497 |