Issue, No.35 (September 2025)

Financial Literacy and Voluntary Savings in the United Kingdom

The article is an outcome of the visiting research stay at LIS that was facilitated by the grant No. APVV-23-0329.

Introduction

Understanding the determinants of voluntary savings is essential for ensuring both individual financial security and broader economic stability. Savings act as a crucial buffer against unexpected financial shocks and play a central role in sustaining living standards throughout retirement (De Nardi et al., 2016). Adami and Gough (2008) show that socio-demographic and economic characteristics such as age, gender, and income significantly shape individuals’ saving patterns, including their propensity to save for retirement. Beyond the influence of socio-economic factors such as income, employment status, and household composition, financial literacy has emerged as a key determinant of individuals’ propensity to save, with higher levels of knowledge linked to more consistent saving behavior and improved long-term financial outcomes (e.g., Lusardi and Mitchell, 2007; Deuflhard et al., 2019).

The importance of voluntary savings has grown in recent decades, as many advanced economies have shifted responsibility for retirement provision increasingly toward individuals by expanding voluntary and workplace pension schemes. In the UK, where rising living costs and economic uncertainty have placed considerable pressure on household incomes (Brewer and Gardiner, 2020), voluntary savings have taken on growing importance as a critical complement to mandatory pension schemes.

While there is substantial evidence on the effects of financial literacy on voluntary pension savings (e.g., Alesie et al., 2011; Cupak et al., 2019) , the specific relationship between financial literacy and savings behavior in the UK remains relatively understudied. In fact, the previous studies looked at the planning for retirement rather than actual savings (see Farrar et al., 2019). Addressing this gap is essential for understanding the relationship between financial awareness and savings decisions in order to design effective policies to improve financial resilience and retirement preparedness.

Therefore, in this short note we explore how the propensity to save may be associated with financial literacy and a range of socio-demographic characteristics. The study draws on data from Wealth and Asset Survey accessed via Luxembourg Wealth Study (LWS) for the United Kingdom in 2019.

Data and Methodology

For the purposes of the analysis, we employ cross-sectional data for the United Kingdom in 2019 accessed via LWS. The data has detailed information on both the asset side and liability side of household portfolio which allows to conduct detailed examination of the determinants of voluntary savings. In addition, the data contains a wide range of socio-demographic characteristics and financial attitudes of individuals. Importantly, the survey data contains a question about the awareness of the concept of risk-reward, which we use as a proxy for financial literacy.

We analyze the relationship with simple linear probability model1 defined by the following equation:

where SAVINGi is a dummy variable that indicates whether or not an i-th individual has any voluntary savings. It takes a value of 1 if a person reports having a positive balance on an individual voluntary pension account (hasip) or having saved and invested income for old-age provisions (basp4) in the last two years, and 0 otherwise.

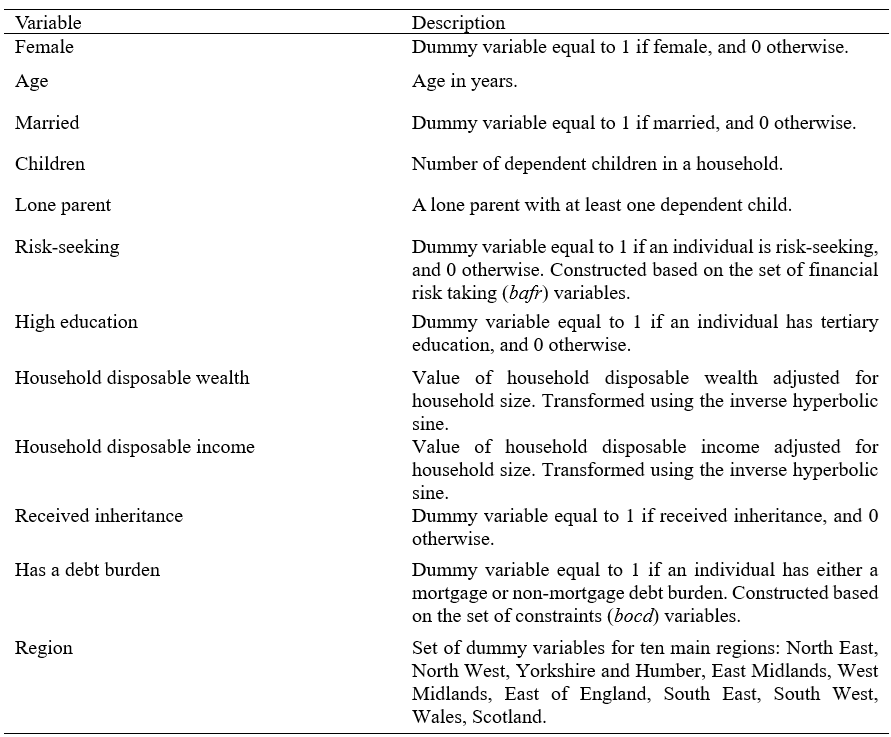

FLi is a dummy variable that indicates whether an individual is financially literate or not. Given the limitations of the available data and unlike in the previous studies considering the financial literacy score (e.g., Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014), our variable is only constructed based on the question related to the concept of risk-reward. The precise question is the following “You can’t expect to get a good return on your money if you don’t take certain risks?” with 4 options: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, “strongly agree”. The dummy variable takes a value of 1 if an individual answers either “agree” or “strongly agree” and 0 otherwise. Following the prior household finance research, Xi represents a vector of socio-demographic and economic factors such as gender, marital status, employment status, income, etc., and δ is a set of dummy variables capturing regional fixed effects. More detailed description of further variables considered in the analysis is available in Table A1.

Results

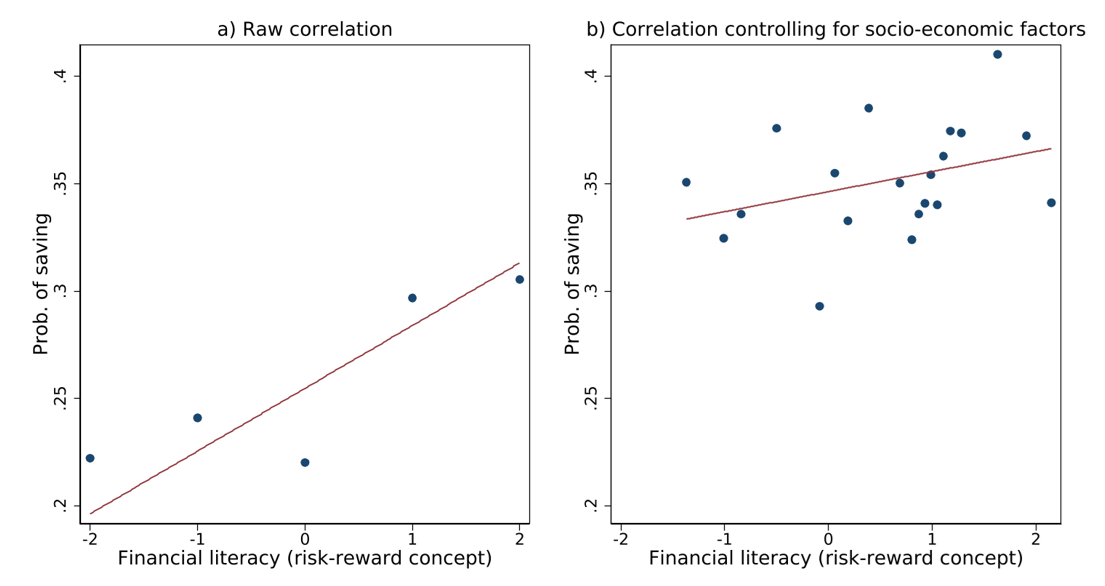

Figure 1 illustrates the baseline relationship between financial literacy and the probability of saving in voluntary pension plans. The left panel shows a positive raw correlation, suggesting that individuals with higher financial literacy – proxied by their ability to correctly answer a risk-return question – tend to have a greater likelihood of saving. The right panel demonstrates that this relationship remains positive after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics such as income, age, education, and household type.

Figure 1: Correlation between financial literacy and the probability of voluntary saving

Notes: Financial literacy variable is recoded as following: -2 – “Strongly disagree”, -1 “Disagree”, 0 “Neither agree nor disagree”, 1 “Agree”, 2 “Strongly agree”. Relationships are estimated using survey weights.

Source: own calculations based on the LWS data.

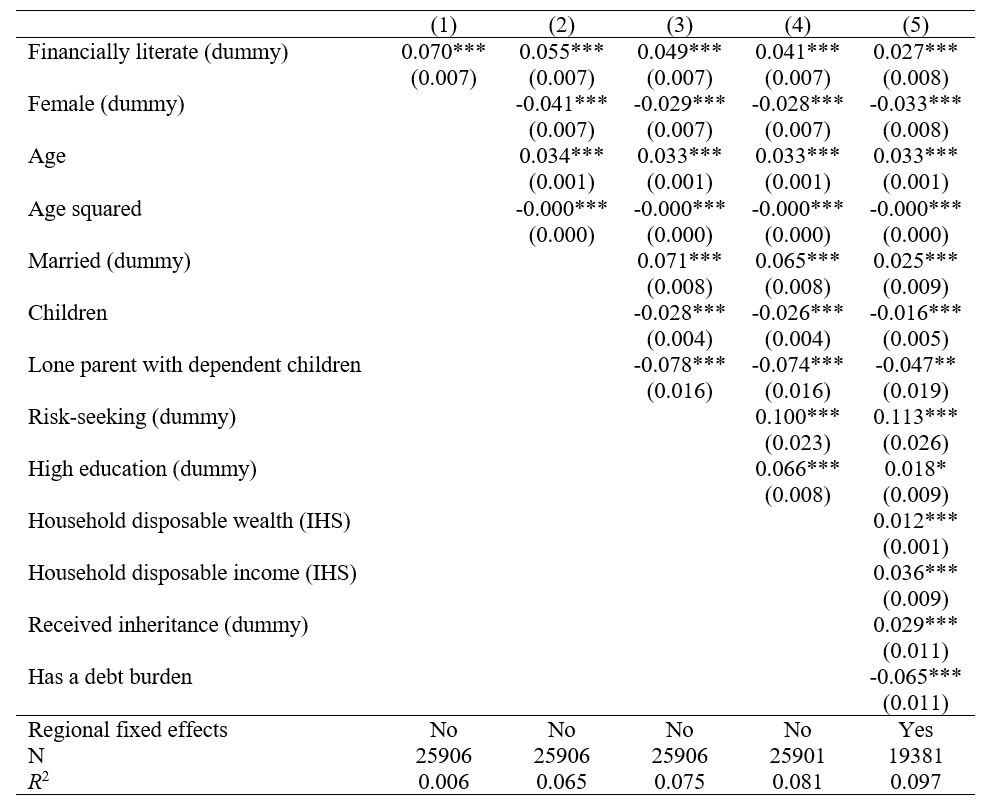

After visual inspection, we now turn to regression estimates. Table 1 presents estimates from linear probability models examining the likelihood of saving in voluntary pension plans. In the baseline model (column 1), which includes only financial literacy, individuals who correctly answer the risk-reward question are 7 percentage points more likely to report saving in a voluntary pension scheme compared to those who do not. This association remains statistically significant and robust across all specifications, though the estimated coefficient declines as additional controls are introduced. In the fully specified model (column 5), which includes socio-demographic variables, household structure, behavioral factors, income, wealth, and regional fixed effects, financially literate individuals are approximately 2.7 percentage points more likely to save. This indicates that financial literacy is positively associated with voluntary saving, even after accounting for a comprehensive set of confounding factors.

Adding gender and age controls in column 2 reduces the effect size to 5.5 percentage points. Notably, women are 4.1 percentage points less likely to save than men, and the probability of saving increases with age but at a diminishing rate—confirming a typical life-cycle pattern.

Columns 3 and 4 include household structure and behavioral characteristics. Being married increases the probability of saving by 6.5–7.1 percentage points, while each additional dependent child reduces the likelihood of saving by approximately 2.6–2.8 percentage points. The effect is more pronounced for lone parents with dependent children, who are 7.4–7.8 percentage points less likely to save, reflecting the added financial pressure and limited saving capacity of this group. Risk preferences also matter: individuals who identify as risk-seeking are about 10–11 percentage points more likely to save voluntarily, indicating the role of behavioral traits in financial decision-making.

Column 5 introduces economic factors such as household income and wealth, alongside regional fixed effects. Higher disposable income and wealth are both positively associated with saving, while having a debt burden is associated with a 6.5 percentage point reduction in the likelihood of saving—one of the strongest negative effects observed. Receiving an inheritance increases the probability of saving by 2.9 percentage points, suggesting that windfall wealth may facilitate long-term financial planning.

Table 1: LPM estimates of the determinants of voluntary pension savings

Note: Regressions are estimated using survey weights. Robust standard errors are reported in parentheses.

* p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01

Source: Own calculations based on the LWS data.

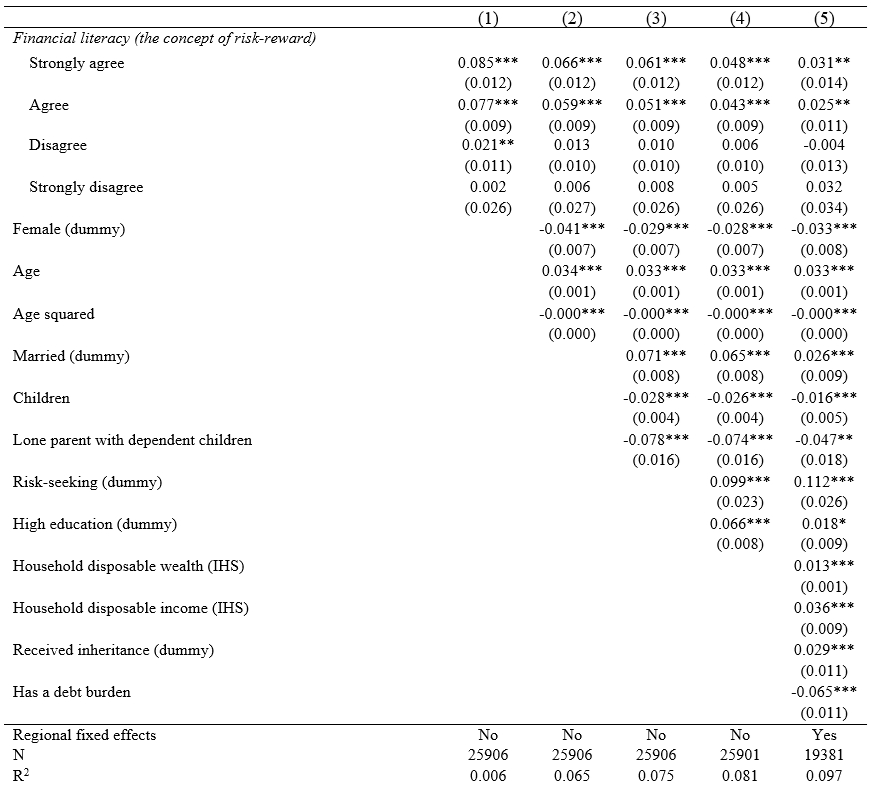

To better capture the link between financial literacy and voluntary saving, the analysis uses a disaggregated measure of financial literacy. Responses to the risk-reward question are kept in four categories, with “neither agree nor disagree” as the reference. This approach helps assess whether the positive association with saving is concentrated among those showing clear understanding. Table 2 introduces coefficient estimates with a disaggregated financial literacy variable. The disaggregated results reveal that the higher likelihood of saving is concentrated among these financially literate groups, while other categories show insignificant differences relative to the reference group.

Overall, the results suggest that financial literacy is positively linked to voluntary pension saving, with the effect concentrated among those demonstrating a clear understanding of the risk-return relationship. These findings are broadly in line with the findings of the previous literature suggesting that there is a positive link between financial literacy and voluntary saving patterns (e.g., Allesie et al., 2011; Deuflhard et al., 2019).

Table 2: LPM estimates of voluntary savings determinants with disaggregated financial literacy

Notes: Regressions are estimated using survey weights. Category “neither agree nor disagree” serves as a reference category for the question on the concept of risk-reward.

* p<0.1, ** p<0.05, *** p<0.01

Source: own calculations based on the LWS data.

Conclusion

This paper investigates the determinants of voluntary savings in the United Kingdom, with a particular focus on the role of financial literacy. Using microdata from the Luxembourg Wealth Study (2019) and applying linear probability models, the analysis provides robust evidence that financial literacy—captured by individuals’ understanding of the risk–reward relationship—is positively associated with the likelihood of saving in voluntary pension plans.

Importantly, this effect is largely driven by individuals who correctly grasp the core principle of risk and return, highlighting the value of even basic financial understanding in shaping long-term saving behavior. While financial literacy plays a distinct and independent role, the analysis also reveals structural barriers that impede saving. In particular, lone parents with dependent children and individuals with debt burdens are significantly less likely to save, underscoring the financial vulnerability of these groups.

Nonetheless, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on cross-sectional data from 2019, which constraints the ability to assess the effect of financial literacy on voluntary savings behavior over time. Second, the measure of financial literacy is limited to a single dimension – understanding of the risk-reward concept – which may not fully capture the complexity of financial knowledge. Despite results not being causal, they may be informative to policy makers attempting to improve financial resilience of individuals and households. However, further research in this area is necessary.

Appendix

Table A1: Description of control variables used in empirical analysis

Source: own processing based on the LWS data.

1 We also checked the robustness of results by using a probit model, and the results are qualitatively very similar.

References

| Adami, R. and Gough, O., 2008. Pension reforms and saving for retirement: comparing the United Kingdom and Italy. Policy Studies, 29(2), pp.119-135. |

| Alessie, R., Van Rooij, M., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10(4), 527-545. |

| Brewer, M. and Gardiner, L., 2020. The initial impact of COVID-19 and policy responses on household incomes. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement_1), pp.S187-S199. |

| De Nardi, M., French, E. and Jones, J.B., 2016. Savings after retirement: A survey. Annual Review of Economics, 8(1), pp.177-204. |

| Deuflhard, F., Georgarakos, D. and Inderst, R., 2019. Financial literacy and savings account returns. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(1), pp.131-164. |

| Farrar, S., Moizer, J., Lean, J., & Hyde, M. (2019). Gender, financial literacy, and preretirement planning in the UK. Journal of Women & Aging, 31(4), 319-339. |

| Lusardi, A. and Mitchell, O.S., 2007. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education: The problems are serious, and remedies are not simple. Business economics, 42(1), pp.35-44. |

| Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5-44. |