Issue, No.31 (September 2024)

Safety Net or Sieve: The Coverage of Minimum Income Schemes and the New Social Risks*

Note: this research partially replicates another analysis on the coverage of minimum income schemes in EU countries by Nardo, Marchal, and Marx (2024). EU-SILC data for 2019 is used.

Reference: Nardo, A, Marchal, M., Marx, I. (2024) “Safety net or sieve: Do Europe’s minimum income schemes reach the poor?,” Working Papers 2402, Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy, University of Antwerp.

1. Understanding the coverage of MIS in light of the new social risks.

Today, nearly all European countries have means-tested minimum income schemes (MIS) in place that guarantee a basic level of income support for the least-well off. Scholars have broadly investigated how these schemes of last resort differ in design, function, and overall effectiveness (e.g. Frazer and Marlier, 2016; Marchal et al., 2021; Immervoll et al., 2015; Natili 2020). Heterogenous performances of MIS are the result of multiple factors, including the design of policy as well as to the complementarity of MIS with first-tier benefits of income maintenance (e.g. Clegg, 2013; Pfeifer, 2013). At the same time, previous research has shown that actual coverage of MIS in Europe is far from complete, due to limits by design, issues of benefit administration, targeting errors, and non-take-up (Figari et al., 2013; Almeida et al., 2022). However, the salience of socio-economic factors has remained underexposed in these studies. Furthermore, the research has mainly focused on macro-level indicators (Tervola et al., 2021; van Vliet and Wang, 2019). Only a marginal literature (Van Mechelen et al., 2016) has empirically explored the link between MIS coverage and the prevalence of social risks among the poor population. This concerns especially the so-called “new social risks”, which resulted from the structural transformations of the labor market and family structure at the end of the 20th century, after the welfare state reached maturity in many countries (Bonoli, 2007). Traditional welfare state, and social insurance in particular, have been found to be ill-equipped to offer adequate protection to those affected by these social risks, who are supposed to rely on last resort means-tested income protection. Examples of such risks are a low level of education in post-industrial economies, single parenthood, or precarious labor market attachment. At the same time, young adults having no or insufficient work histories will often lack social insurance entitlements.

Only few comparative analyses have investigated the profiles of MIS beneficiaries at the micro-level (Immervoll et al., 2022). Even less attention has been dedicated to the poor population that is left uncovered from income support. This poses an important gap in our understanding of the effectiveness of MIS and of the actual targeting of these benefits.

2. Methodology of the research

Using the micro-data from the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database for 17 European countries1, we explore the recipiency (also known as the effective or actual coverage – van Oorschot, 2013) of last resort means-tested income support. For this purpose, we define the recipiency rate of MIS as the ratio of MIS beneficiaries among the pre-transfer poor working-age population, setting the poverty threshold at 60% of the median equivalized household income. First, we show to what extent MIS succeed in covering the gaps left by the welfare state – especially social insurance – or whether substantial numbers are left unprotected. Then, we focus on the profiles of both MIS beneficiaries and the uncovered poor. As such, we investigate the prevalence of a selection of new social risks (single-parenthood, foreign citizenship, low education, non-standard employment, and young age) and one typical old social risk (disability) among different groups of the pre-transfer poor population.

As eligibility and generosity of the transfers generally depend on household-level characteristics and living conditions, and as the information about MIS resources is only provided at household level, we consider all individuals in a beneficiary household as MIS recipients. While, in principle, this choice could amount to an overestimation of benefit coverage (Otto, 2018), such potential effect is reduced by our choice of considering only the working-age population (between 16 and 64 years-old). We consider a household to be beneficiary when the income from the relevant social assistance variable is higher than zero (Tervola et al., 2021).

In this research, we principally distinguish between those receiving general minimum income support (MIS) and those receiving social insurance (SI). Some income replacement benefits cannot be categorized as fully functionally equivalent to a minimal last resort benefit, nor as contributory social insurance benefits. We therefore include an additional category, of those covered by “other income assistance” benefits. To identify the uncovered, we zoom in on those of the working age pre-transfer poor population that do not receive any of the three aforementioned types of income replacement benefits. That does however not preclude them from receiving minor, supplementary benefits, especially universal transfers whose receipt is independent from the living conditions of the household.

3. Results and discussion

a. The coverage of MIS in European welfare states

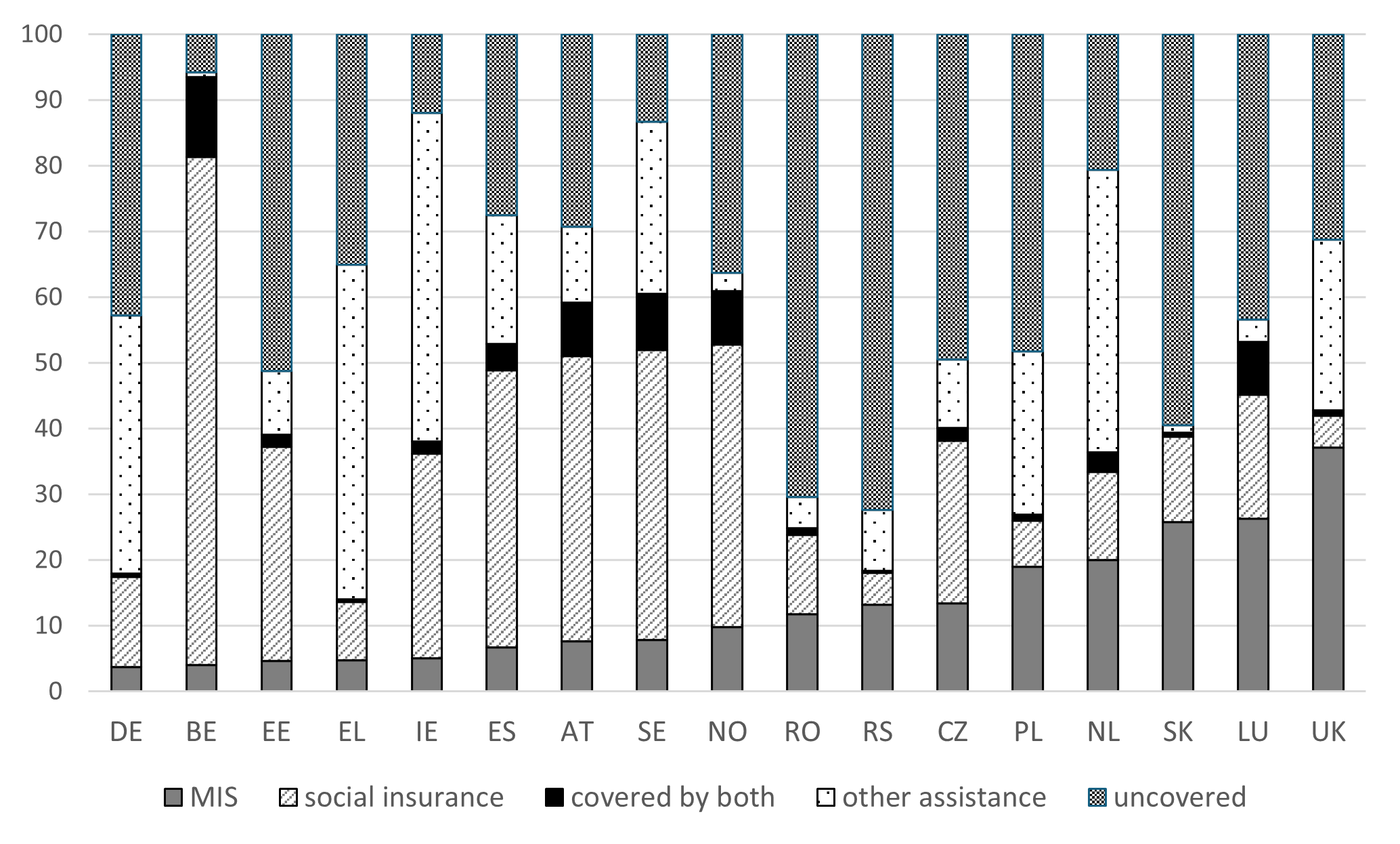

Figure 1 splits the working-age population at risk of poverty before receiving social benefits in five categories: i) individuals receiving only last-resort income replacement benefits (MIS), ii) only insurance-based income replacement support (SI), including pensions, sickness, disability, survivor, and unemployment benefits, iii) receiving both MIS and SI income replacement, iv) other assistance-based cash benefits and v) individuals left uncovered by any of these benefits. We find important variation in the way national welfare states cover the pre-transfer poor of working-age.

A first observation from Figure 1 is the large variation in MI coverage rates (dark-grey bars): in most countries, the scope of MIS is very limited, covering – alone – less than the 10% of the pre-transfer poor population. However, in a limited set of countries – specifically Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden – a sizable share of the pre-transfer poor population is covered by a combination of social insurance and MI benefits (black bars). This points towards a different role that MI may play in these countries, as a benefit that is also intended to top-up low incomes, whether those are from work or from (partial) social insurance benefits.

Figure 1. Share of pre-transfer poor population left uncovered by income replacement and composition of income support for those covered in 27 European countries.

Notes:The countries are ordered by the share of pre-transfer poor receiving only minimum income benefits (“MIS”).

Source: own calculations based on LIS data (2016-2019).

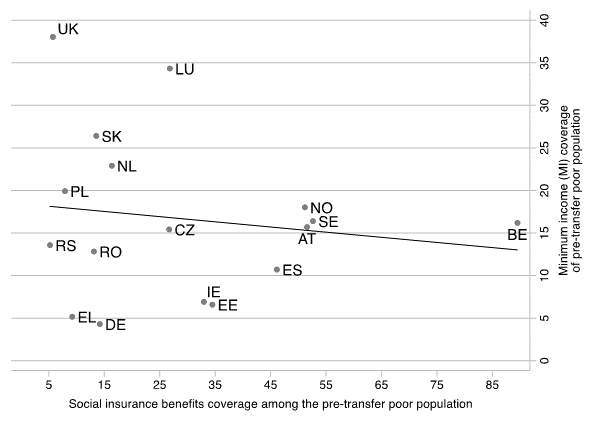

MIS play a more relevant role in the UK, Luxembourg, Slovakia, and, less, in the Netherlands and Poland. The share of (pre-transfer) poor individuals not covered by income replacement benefits differs quite substantially between countries, ranging from less than 10% (Belgium) to 70% (Romania and Serbia), with many countries covering less than 60% of the pre-transfer poor population with income replacement benefits. Contrarily to what could be expected, the coverage rate of last resort income support and the share of uncovered poor are not inversely correlated. In fact, in most countries, the (large) majority of the covered pre-transfer poor is catered for either by social insurance-based benefits (dashed bars) or by other forms of social assistance. To complement this picture, Figure 2 shows only partial evidence for the expectation that social insurance (SI) and MI act as “communicating vessels” (Pfeifer, 2013), so that MIS only take a relevant role in those welfare states where first-tier benefits are less generous.

Figure 2 Correlation among the coverage rates of Social Insurance – x-axis – and of Minimum Income – y-axis – among the pre-transfer poor in working-age.

Source:own calculations based on LIS data (2016-2019).

b. The coverage of MIS in light of the “new social risks”: a safety net or sieve?

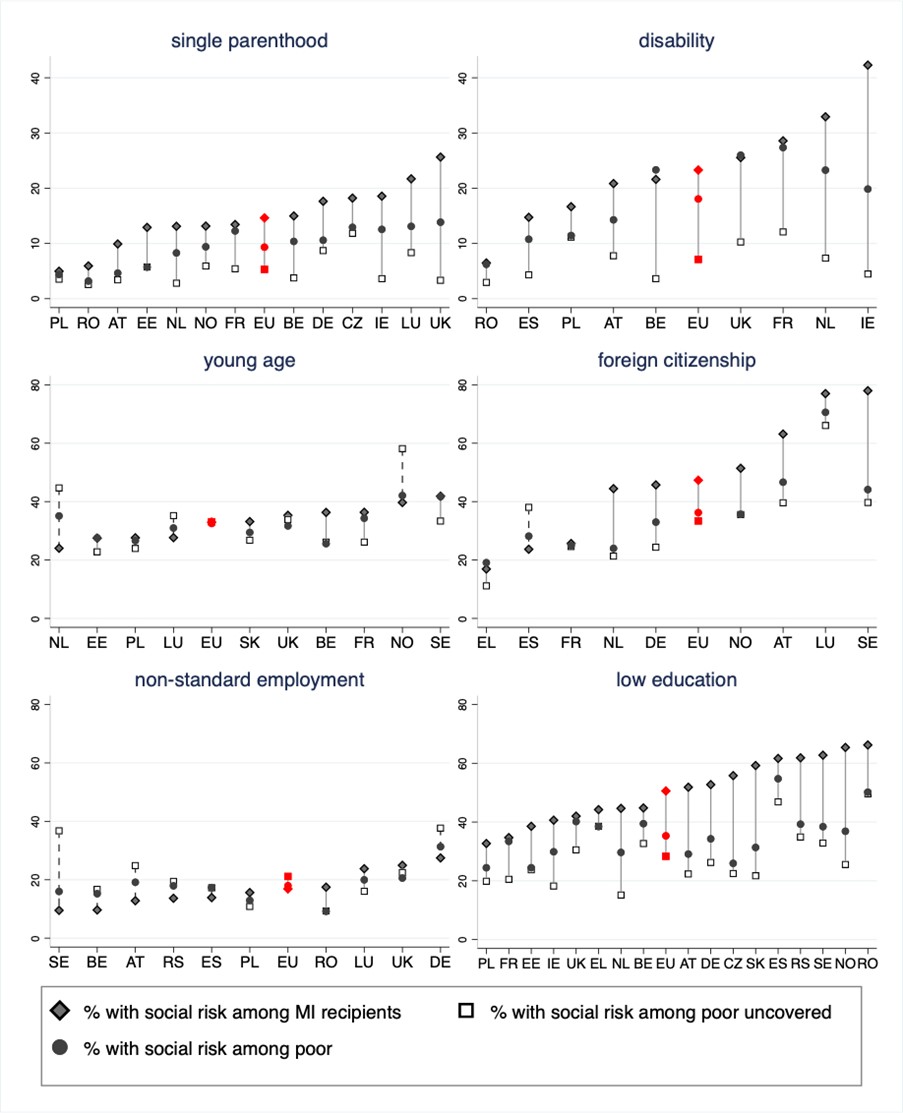

Next, we adopt a social risk lens to gain a deeper understanding of the profiles of those (un)covered by MI. Figure 3 shows the extent to which new risk groups are represented among those taking up MI and among the uncovered, relative to their presence in the pre-transfer poor population2. Overall, MI receipt among young people, non-standard workers, and – to a lower extent – single parents are in line with their shares among the pre-transfer poor population. Interestingly, those with low education are overrepresented among the MI population, as are – for some countries – those with foreign citizenship. On the other side, those with new social risks are often underrepresented among the uncovered, again relatively to their shares in the pre-transfer poor population. The cases of the young individuals and those in non-standard work represent the main exceptions. We find that that the young are overrepresented among the uncovered in Norway, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. We also see large country differences in coverage for those in non-standard employment, although it is hard to draw firm conclusions from this.

Figure 3 also reveals interesting deviations from the general pattern for those with foreign citizenship. In most countries, those with foreign citizenship represent larger shares of the social assistance population as compared to the uncovered (Spain is the only exception). Yet the extent to which this is true varies greatly. Sweden stands out as a country with a very high share of social assistance recipients having a foreign citizenship, far higher than their share among the poor population, and especially than the uncovered. A similar pattern, though far less explicitly so, appears in the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria.

Finally, those with a disability, who we included as a “typical old social risk” reference group, only represent a very small share of the uncovered, but constitute far larger shares of those covered by MI.

Figure 3. Share of working-age individuals experiencing a social risk among different segments of the pre-transfer poor working age population.

Notes:The European: average (“EU”, but including extra-EU countries) is calculated for the countries included in each graph.

Disability: persons with self-assessed severe activity limitation; Young age: working-age persons < 30 years; Foreign citizenship: citizenship differs from country of residence; Single parenthood: living without a partner and with one or more children below age 25; Non-standard employment: part-time; self-employed; working as pupil, student, further training, unpaid work experience, or those with temporary contracts. Low-education: no higher secondary education.

Source: own calculations based on LIS data (2016-2019).

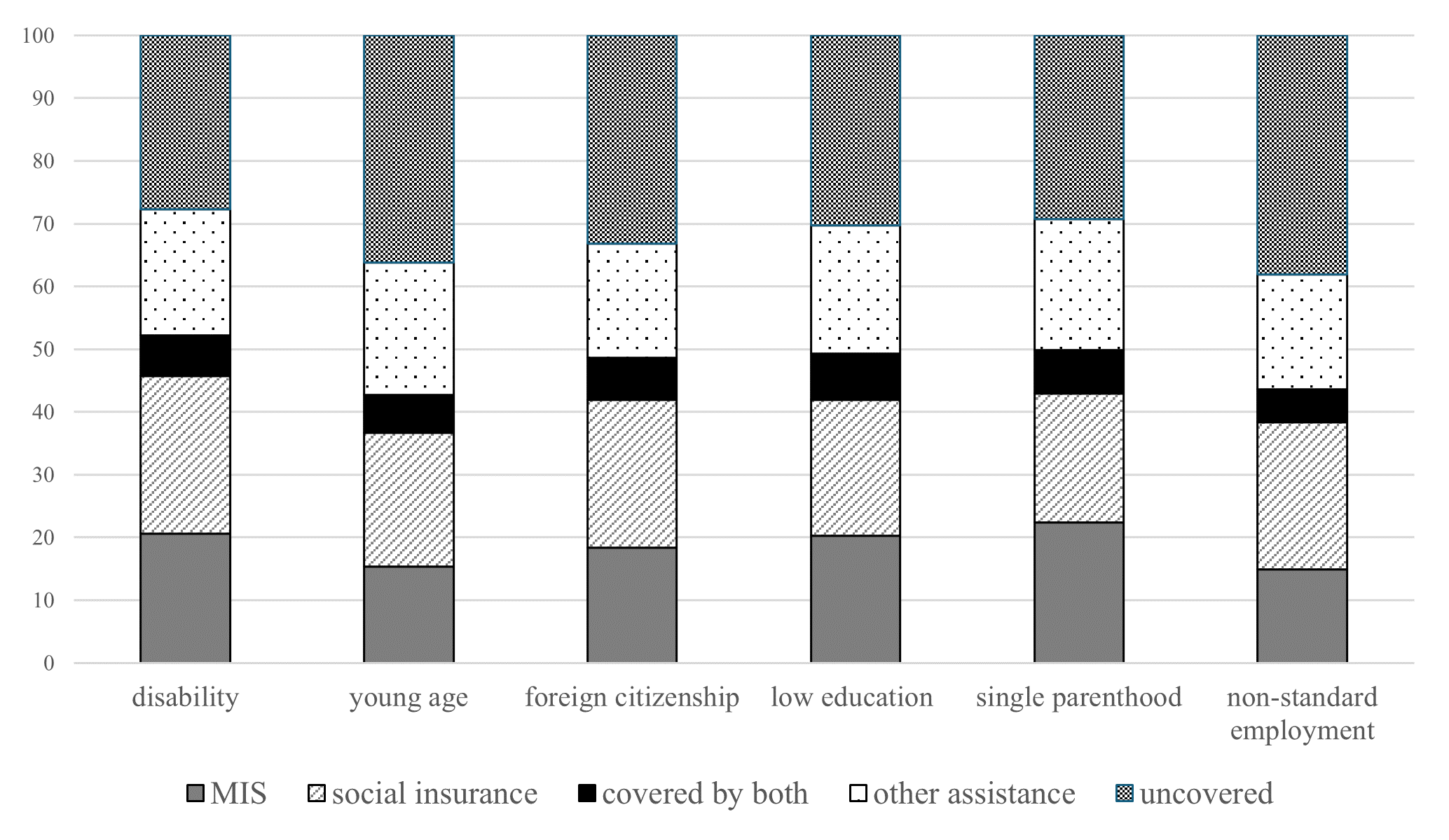

In Figure 4 we show to what extent social risks are covered by different types of provisions (MI, SI, combinations or other) or if, instead, they are left uncovered. For illustration purpose, we show the average results at European level, including all the countries with valid results for the relevant variables (see the cross-country results in online Annex). In line with the above observations, the disabled poor are generally more covered, and more frequently by social insurance. Risks that one could think of as new social risks, are in general less often covered, and if they are, this is more often through MIS. This seems to be especially the case for the population groups low-education and single-parenthood. Interestingly, and again in line with the observations above, coverage rates for non-standard employment and young age are lower than those for single parents, low education and foreign citizenship.

Figure 4. Coverage among the pre-transfer poor confronted with a social risk by different types of social benefits, average among 19 European countries.

Notes: The average is calculated including all the countries with valid results for each social group (see figure A.4 in Annex). The average is calculated among 18 countries for foreign citizenship (RO missing) and non-standard employment (NO missing). See the note for Figure 3 for the definition and operationalization of the social risks.

Source: own calculations based on LIS data (2016-2019).

4. Conclusions

This research uses LIS data to shed new light on the recipiency of last resort minimum income support (MIS) among the working-aged people in Europe who are at risk of poverty. First, we show that the share of pre-transfer poor individuals effectively covered by means-tested income support varies a lot, being well below 20 per cent in about half of the European countries. Then, large shares of the needy are uncovered by either scheme. The share of pre-transfer poor individuals who are left uncovered by both social insurance and minimum income benefits ranges from less than 20 per cent in Belgium to over 70 per cent in Romania. In many countries less than 50 per cent of the pre-transfer poor population is uncovered by any of the income replacement benefits included in this study. Finally, we do find that those confronted with new social risks form a large part of the MI beneficiary population. Still, and importantly, they are also overrepresented among the uncovered, specifically in the case of young people and those in non-standard employment. Yet patterns are not very consistent, pointing to manifold national idiosyncrasies in coverage mechanisms. Therefore, a more detailed focus on each national case is needed to understand the factors explaining the differences here spotted. Furthermore, the reasons behind the gaps in the coverage of MIS for people experiencing new social risks should be explored. In that sense, the national institutional features – e.g. the setting of national welfare states and the design of MIS – and of contextual dynamics are of crucial importance to understand the outputs and outcomes of MIS. Methodologically, this will require both the use of microsimulation techniques and further investigation of the recipiency of social benefits.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 For each country, we use the last version of the data released before the Covid-19 pandemic (2020). The versions of the data range from 2016 to 2019.

2 Figure 3 shows also the average (“EU”) for those countries for which we find significant differences in the presence of persons confronted with specific social risks among the (pre-transfer poor) MI and uncovered population (p<0.05; t-test).

References

| Almeida V, Poli S, and Hernández A (2022). The effectiveness of Minimum Income schemes in the EU. |

| Bahle T, Hubl V, and Pfeifer M (2011). The last safety net. A handbook of minimum income protection in Europe, Bristol Policy Press. |

| Bonoli G (2007). Time Matters: Postindustrialization, New Social Risks, and Welfare State Adaptation in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 40(5), 495–520. |

| Clegg D (2013). Dynamics and varieties of active inclusion: A five-country comparison. Deliverable D5, 6. |

| Figari F, Matsaganis M, and Sutherland H (2013). Are European social safety nets tight enough? Coverage and adequacy of Minimum Income schemes in 14 EU countries: Are European social safety nets tight enough? International Journal of Social Welfare, 22(1), 3–14. |

| Frazer H and Marlier E (2016). Minimum income schemes in Europe: A study of national policies 2015. Publications Office. |

| Immervoll H, Hyee R, Fernandez R, and Lee J (2022). How Reliable are Social Safety Nets? Value and Accessibility in Situations of Acute Economic Need. SSRN Electronic Journal. |

| Immervoll H, Jenkins SP, and Königs S (2015). Are Recipients of Social Assistance ‘Benefit Dependent’? Concepts, Measurement and Results for Selected Countries. SSRN Electronic Journal. |

| Kauppinen TM, Angelin A, Lorentzen T, Bäckman O, Salonen T, Moisio P, and Dahl E (2014). Social background and life-course risks as determinants of social assistance receipt among young adults in Sweden, Norway and Finland. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(3), 273–288. |

| Marchal S, Kuypers S, Marx I, and Verbist G (2021). But what about that nice house you own? The impact of asset tests in minimum income schemes in Europe: An empirical exploration. Journal of European Social Policy, 31(1), 44–61. |

| Natili M (2020). Worlds of last-resort safety nets? A proposed typology of minimum income schemes in Europe. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 36(1), 57–75. |

| Otto A (2018). A Benefit Recipiency Approach to Analysing Differences and Similarities in European Welfare Provision. Social Indicators Research, 137(2), 765–788. |

| Pfeifer M (2013). Comparing unemployment protection and social assistance in 14 European countries. Four worlds of protection for people of working age. International Journal of Social Welfare, 21(1), 13–25. |

| Taylor-Gooby P (2004). New risks and social change. New Risks, New Welfare: The Transformation of the European Welfare State, 1–28. |

| Tervola J, Mesiäislehto M, and Ollonqvist J (2021). Smaller net or just fewer to catch? Disentangling the causes for the varying sizes of minimum income schemes. International Journal of Social Welfare. |

| Van Mechelen N, Zamora D, and Cantillon B (2016). De groei en diversificatie van de bijstandspopulatie. In 40 jaar OCMW en bijstand.-Leuven, 2016 (pp. 13–32). |

| Van Oorschot W (2013). Comparative Welfare State Analysis with Survey-Based Benefit: Recipiency Data: The ‘Dependent Variable Problem’ Revisited. European Journal of Social Security, 15(3), 224–248. |

| van Vliet O, and Wang J (2019). The political economy of social assistance and minimum income benefits: A comparative analysis across 26 OECD countries. Comparative European Politics, 17(1), 49–71. |