Issue, No.9 (March 2019)

The Consequences of Decentralization: Inequality in Safety Net Provision in the Post–Welfare Reform Era

This article is excerpted from Bruch, Sarah K., Marcia K. Meyers, and Janet C. Gornick. 2018. “The Consequences of Decentralization: Inequality in Safety Net Provision in the Post-Welfare Reform Era.” Social Service Review 92(1): 3-35.

In recent years, inequality has received increasing attention in political, policy, and academic circles. In the United States, the conversation has been overwhelmingly national in scope. This national focus misses another enormously consequential axis of American inequality — that is, how decentralized provision of social and health assistance has shaped geographic inequalities across the 50 US states.

In this article, we shine a spotlight on how federalism produces inequality through the decentralized policy designs of safety net programs. To do so, we consider two research questions. First, is the magnitude of cross-state variation in provision associated with the degree of state discretion in administration, financing, or rule making? We examine 10 federal-state programs that make up much of the safety net for low-income or unemployed adults and their families. Second, has there been convergence or divergence in safety net programs from 1994 to 2014?

The decentralized US safety net & cross-state inequality in safety net provision

Social provision in the US is unequal by design, providing tiered and categorically-based assistance that varies — across jurisdictions and citizens — in both quantity and quality. Programs in the top tier are standardized or uniform in terms of their benefits and broad in terms of their coverage; programs in the bottom tier — the focus of our analysis — are narrowly targeted, means-tested, and more variable in terms of the benefits they provide and which potentially eligible populations receive their benefits. While programs in the top tier are financed and administered at the federal level, the majority of the programs in the bottom tier have some degree of devolved authority or discretion to lower levels of government.

This decentralized structure has produced substantial inequalities in provisions across states and across populations within states (Meyers, Gornick, and Peck 2001; Allard 2008; Lobao and Kraybill 2009; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). The extent and implications of the decentralized structure are among the most underappreciated features of the US welfare state (Pierson 1995; Howard 1999). Thus, we leverage the decentralization of US safety net provision to assess the degree of cross-state inequality in provision. We begin by examining the magnitude of cross-state variation in the generosity and inclusiveness of assistance provided through safety net programs that differ in the extent of state discretion for financing, rule-making, or administration.

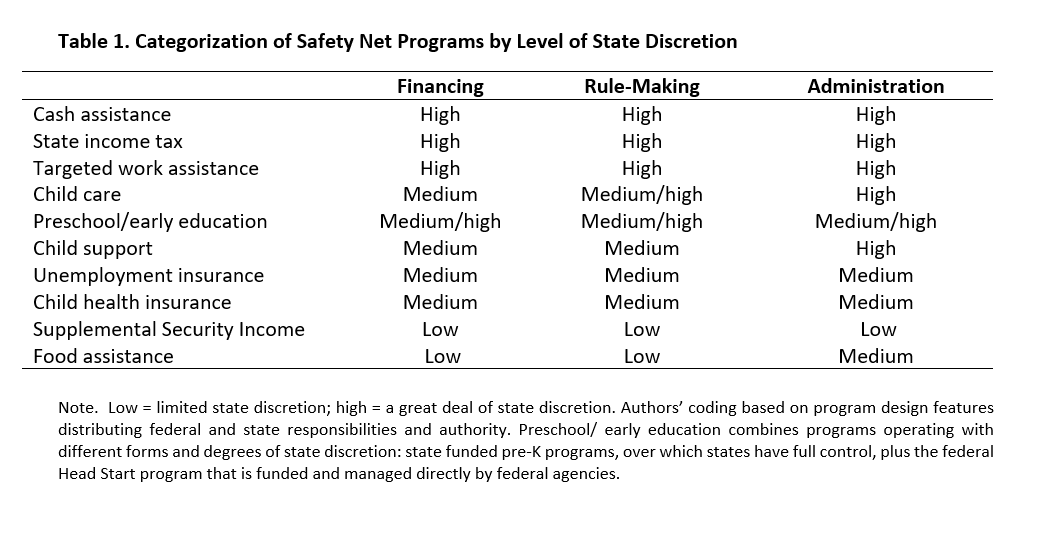

To examine this, we identify 10 primary federal-state safety net programs and categorize the extent of state discretion created through policy design in three domains: (1) financial, joint federal-state funding arrangements, partial state funding for programs, or state discretion in spending federal funds; (2) rule-making authority, authority to determine rules regarding eligibility, benefits, and other aspects of the program; and (3) administration, flexibility and discretion in the implementation, management, and frontline delivery of assistance.

We formulate two expectations. First, we expect less inequality in the generosity of benefits in programs that are primarily federally funded and correspondingly greater inequality in those programs in which states have more responsibility for financing and exercise more discretion in setting benefit levels. Second, we expect that state inequality in inclusiveness will be highest in programs for which states claim high levels of both rule-making authority and administrative flexibility.

Data and measures

We use the State Safety Net Policy (SSNP) data set, a unique data set that the authors have assembled from publicly-accessible state and federal administrative records, secondary sources of these records, and original population estimates calculated using the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS). These data include 10 federal-state programs for low-income or unemployed working-age adults and their families: cash assistance (AFDC/TANF), food assistance (Food Stamps/SNAP), child health insurance (Medicaid and CHIP), child support enforcement, child care subsidies (CCBG/CCDF and TANF), early childhood education (Head Start and state pre-K programs), Unemployment Insurance (UI), targeted work assistance through AFDC/TANF, child disability assistance (SSI), and state income taxes for families at the poverty line.

For each type of assistance, generosity is calculated by dividing total benefit spending (federal, state, or both, as appropriate) by a state’s caseload or number of recipients. For a detailed overview of measure construction, see Bruch et al. 2018. The generosity measures are adjusted to constant (2012) dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index Research Series (CPI-U-RS). Inclusion is calculated by dividing the number of program recipients in a state by the number of potentially needy individuals or families in the state. For means-tested programs, the estimate of the potentially needy is the number of individuals or families who (a) fall into categorically-eligible groups, and (b) have market (or pre-tax, pre-transfer) incomes below the federal poverty threshold or below some percentage of the threshold depending on the income eligibility criteria of the program (estimated using 3-year moving averages from the ASEC of the CPS).

Analytical method

To answer our first research question concerning the extent of variation in social safety net provision across the US states, we estimate several measures of variation and dispersion. To describe the magnitude of differences across states in a readily interpretable metric, we provide the absolute values observed at different points in the distribution of states (90th and 10th percentiles). To estimate the level of cross-state variation or inequality, we estimate the range, variance, and coefficient of variation (COV). In order to assess the correspondence between the extent of state discretion and the magnitude of cross-state variation, we categorize each program as providing high, medium, or low levels of discretion (see Table 1).

To answer our second research question, we use 20 years of data to compare the trajectories of change in cross-state variation across programs. The analysis of change over time examines two aspects of convergence: the degree or magnitude of change, observed as change in variation, and the location of change, observed by examining change at different points in the distribution. The degree of convergence is assessed by comparing changes in the COV from 1994 to 2014. Examining all three together (COV, variance, and mean) provides insight into why the COV is increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable over time. Finally, the location of convergence is assessed by comparing the values at the 10th and 90th percentiles, which allows us to identify whether there is evidence of states at low levels of provision catching up with others, or if states at high levels of provision are reducing their levels of provision more than other states.

Results – similar risks, but unequal risk protection

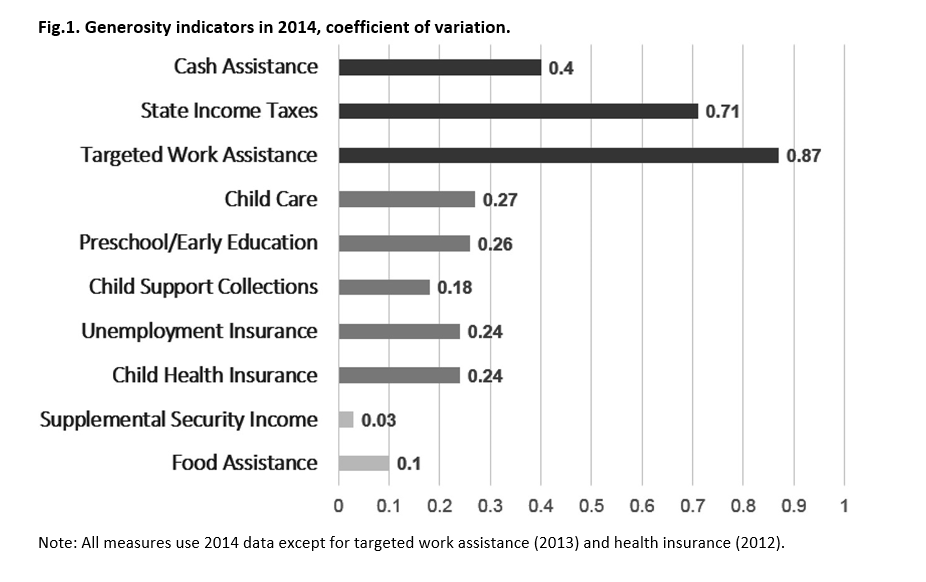

As we expected, in 2014 we observe greater variation in the generosity of benefits in those programs over which states have greater financing responsibility and control (see Fig. 1). The COV measures are largest in the three programs that have high levels of state discretion over funding (cash assistance, state income taxes, and targeted work assistance). In contrast, the two programs with the least cross-state variation are largely or entirely federally funded, leaving states with limited discretion for determining total spending or individual benefit levels: food assistance and SSI. In principle, states may supplement the SSI child benefits, but currently 18 states do not supplement the federal benefit for children, and four states only supplement benefits for specific types of disabilities.

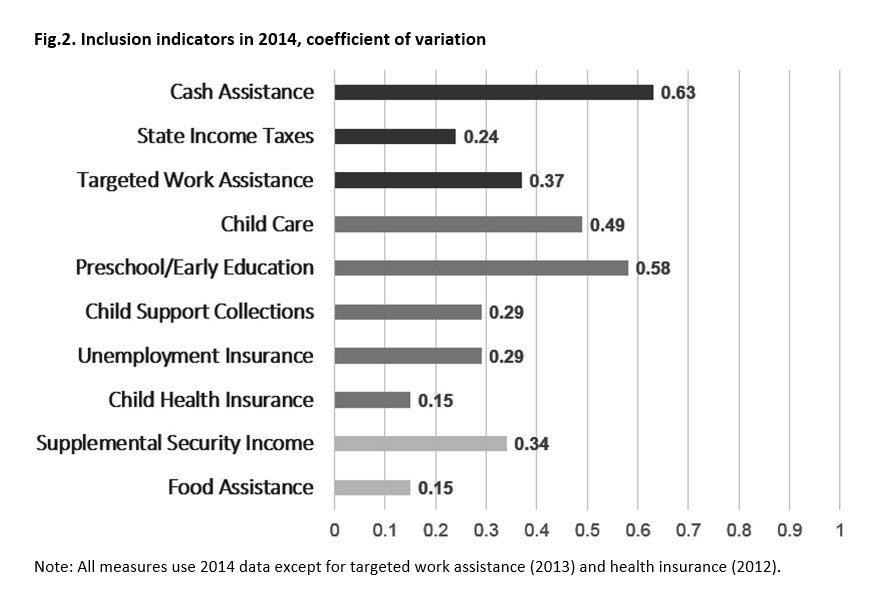

The extent of cross-state variation by program also conforms to our second expectation, that variation in inclusiveness would be greatest in programs over which states exercise greater discretion in rule-making and administration (see Fig. 2). Five of the 10 programs are characterized by high levels of both rule-making authority and administrative flexibility; these programs are also among the most variable across states: cash assistance, preschool/early education, child care, and targeted work assistance. High levels of state variation in the TANF-related programs is not surprising given the explicit devolution of authority to set eligibility criteria and rules in the TANF block grant (Schott et al. 2015). The variation in inclusiveness of preschool/early education programs reflects the combination of Head Start, a federally-administered program, and state-initiated and managed pre-K programs, which vary dramatically across states (Barnett et al. 2015). In contrast, the programs with the least variation in the inclusiveness of receipt — food assistance and health insurance — are both subject to standard federal eligibility criteria and require states to seek waivers for significant deviations from these criteria, and they are also subject to direct federal oversight and monitoring.

Inequalities across states are even more pronounced in the inclusiveness of social safety net programs. Although targeted on the neediest, most programs serve only a fraction of those at risk. In seven of the 10 programs, the average rate of inclusion is less than half in 2014, and even states at the 90th percentile of inclusiveness served fewer than two-thirds of those in need. Only two programs — food assistance and children’s health insurance — effectively reached not only those in poverty but a share of those over the federal poverty line. With the exception of these two relatively expansive programs, levels of inclusion are generally low and vary by 50 percent or more between the more and less inclusive states. It is crucial to note that these differences create geographic inequalities in the treatment of similar claimants and, by allowing some states to provide very low benefits to a small fraction of the needy, exacerbate the weakness of the safety net as a whole.

Taken together, these findings reveal substantial cross-state variation in safety net provision, resulting in highly unequal access and benefits provided through the same programs in different states. Direct federal funding and nationally uniform eligibility criteria appear to result in lower levels of geographic inequality in state provision. Even in programs with consistent federal rules, however, state administrative actions appear to introduce variation in treatment, particularly in access to benefits. The weaker the federal role, the further apart are the states with respect to both the share of the needy they help and the level of assistance they provide.

Convergence, divergence, or stasis in state provisions

Expectation of both divergence and convergence can be derived from theories of federalism that point to the ongoing, strategic competition for policy control within multilevel governance systems. Despite significant changes in levels of provision between 1994 and 2014, as measured by the generosity of benefits and inclusion of the needy, the extent of state variation did not change significantly on most measures (results not shown). This consistency in the magnitude of state variation supports the expectation from institutional theory of path dependence and feed-forward effects, resulting in stability over time in state approaches.

However, the majority of the exceptions to this pattern of stability were in programs directly affected by federal legislation in the mid- to late 1990s (Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA)) which increased state control over policy in some programs while also imposing more centralized control in others. We find divergence or increased state variation in the inclusiveness of two programs (cash assistance and child care) in which the conversion from individual entitlements to block grants in PRWORA increased state discretion. We also find convergence or a narrowing of state variation in programs for which federal actions mandated (child support collections) or incentivized (child health insurance) greater inclusion of the needy.

Conclusion

The decentralized structure of the safety net is one of the most crucial yet least carefully studied structural design features of the US welfare state, and it has dramatic consequences in terms of inequalities in social provision across the states. Using state-level measures to examine geographic inequality in safety net programs, we shed new light on the potential consequences of the decentralized structure of assistance for working-age adults and families.

The most striking finding of our analysis is the extent and persistence of state inequality. Scholars have long observed that inequality is an inevitable outcome of a federalist system, especially in the absence of fiscal redistribution. Nevertheless, the extent of inequality in the US safety net has rarely been assessed across the weakly coordinated system of numerous separate programs that make up the American welfare state. When we undertake such an assessment using comparable state-level measures of generosity and inclusion, we find unequal treatment of individuals and households with similar needs who live in different jurisdictions. We also find that the magnitude of cross-state inequality in provision corresponds to the level of state discretion in financing, rule-making, and administration. The highest levels of inequality are observed in those programs for which states have the highest level of financial responsibility and greater rule-making and administrative autonomy, especially with regard to the inclusiveness of program receipt. At the same time, the vast majority of programs can be characterized as having relatively stable levels of cross-state inequality in provision during recent decades. This is likely a result of the substantial path dependence or feed-forward effects of the initial policy designs that established particular federal-state arrangements in terms of responsibility for financing, rule-making, and administration.

The implication of these findings is that designing policies with state discretion in financing, rule-making, or administration is likely to lead to greater levels of cross-state inequality in provision than a design in which state discretion is limited. While political ideology or economic conditions may influence the policy diffusion and adoption process, attention must also be paid to how the policy itself is structured. Given the magnitude and general stability of state inequalities in provision, our findings suggest that any change in the policy environment that is intended to reduce such inequality would need to include reducing the level of state discretion in these programs.

References

| Allard, S. (2008). Out of Reach: Place, Poverty, and the New American Welfare State. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. |

| Barnett, W. S, M. E. Carolan, J. H. Squires, K. C. Brown, and M. Horowitz (2015). “The State of Preschool 2014: State Preschool Yearbook.” National Institute for Early Education Research, New Brunswick, NJ. |

| Bruch, Sarah K., M. K. Meyers, and J. C. Gornick (2018). “The Consequences of Decentralization: Inequality in Safety Net Provision in the Post-Welfare Reform Era.” Social Service Review 92(1): 3-35. |

| Howard, C. (1999). “The American Welfare State, or States?” Political Research Quarterly 52 (2): 421–42. |

| Lobao, L., and David Kraybill (2009). “Poverty and Local Governments: Economic Development and Community Service Provision in an Era of Decentralization.” Growth and Change 40 (3): 418–51. |

| Meyers, M. K., J. C. Gornick, and L. R. Peck (2001). “Packaging Support for Low-Income Families: Policy Variation across the United States.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 20 (3): 457–83. |

| Pierson, P. (1995). “Fragmented Welfare States: Federal Institutions and the Development of Social Policy.” Governance: An International Journal of Policy and Administration 8 (4): 449–78. |

| Schott, L., L. Pavetti, and I. Floyd (2015). “How States Use Federal and State Funds under the TANF Block Grant.” Report. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Washington, DC. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/how-states-use-federal-and-state-funds-under-the-tanf-block-grant |

| Soss, J., R. C. Fording, and S. F. Schram (2011). Disciplining the Poor: Neoliberal Paternalism and the Persistent Power of Race. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |