Issue, No.10 (June 2019)

Informal activity on the labour market – a new LIS variable

According to ILO estimations, the informal economy, in its diverse forms, extends to more than half of the world labour force and to more than 90 percent of all Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs), with a preponderance in emerging economies. Recognising the importance of the commitment to decent work for all workers, with the new template LIS introduced a new variable, informal, aimed at measuring informal activities on the labour market. Previously, information on informal activities could be found mostly in the LIS variable notoff_c (country-specific information about unofficial/non-registered/untaxed work) and in some cases in oddjob_c (country-specific information about irregular/casual/odd jobs for pay), however, as these were country-specific variables, codes and contents varied considerably across countries. The new standardised variable informal is a dichotomous variable, whereby any indication of informal activity is denoted with the value 1. Although the codes are standardised, users of the LIS/LWS databases need to use this variable with care, as the concept of informal labour market activity and the collected information differs largely from country to country.

The objective of this article is twofold. First, we will briefly describe the conceptual idea of informal labour market activities more broadly, with a specific focus on the difference between dependent and self-employed persons affected by informal activities, while also clarifying how this concept can be captured with the LIS data. Secondly, we will show some descriptive numbers based on the new LIS variable concerning the prevalence of informal activities among persons with different education levels and among those working in different economic sectors, looking separately at dependent workers versus self-employed persons.

According to a report by the ILO, informal economy refers to “all economic activities by workers and economic units that are – in law or in practice – not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements”, a definition that covers a wide variety of situations. First, one needs to acknowledge a clear difference between informal activities in dependent as opposed to self-employed work. For employees ‘informal’ mostly refers to situations where a work contract is absent, or where there is non-compliance with legal rights on the part of the employers, non-registration in the social security system, or work in unregistered businesses, or even the production of illegal goods or services. As diverse as these situations may seem, they overlap to a large extent, in other words the identified group shares several characteristics at the same time. For the self-employed too, the concept of informality is varied. Thus, being informal could refer to operating an unregistered business, to non-payment of taxes or of contributions to the social security system, in contravention of the law; persons carrying out non-paid activities for the well-being of the household (such as farming for own consumption) can also be included in the definition of informal workers.

Since there are no international best standard practices as to how exactly informal activity should be measured, the way the information is collected varies considerably across countries and surveys. In order to achieve the best comparable indication of informality while still capturing the majority of informal workers, LIS has decided to adopt a clear definition of informality. As regards employees, are considered as informal those who fulfil at least one of the following criteria: i) work without a work contract, ii) do not contribute to the social security system, iii) work in an unregistered business, iv) do not benefit from legal rights (right to pension, paid leave, etc.) v) earn an under-declared wage. For the self-employed the indication of informality is restricted to those: i) who own an unregistered business when the legislation in the country requires them to register it, and/or ii) who do not pay taxes and/or contributions if they have to pay them. We do not aim to flag those who produce goods and services only for their own consumption.

As a result, the contents of the LIS informal variable are derived from a variety of different questions. In Mexico, Colombia and Peru for example, employees are asked about the existence of a work contract (albeit with some differences in formulation and scope), while in Brazil, Chile, Estonia, Greece, Guatemala, Taiwan and Uruguay they are asked whether they have social security insurance; in South Africa informal refers to employees working in non-registered jobs, and in Russia the respondents are asked if they work in the informal sector versus the formal one. For the self-employed the content is more frequently standardised, as it refers mostly to having an unregistered business (Estonia, Panama, Paraguay, Uruguay, South Africa). For the other countries informal refers mostly to not contributing to social security system. For a detailed description of exact contents of the variable in specific datasets, LIS/LWS users are advised to consult METIS.

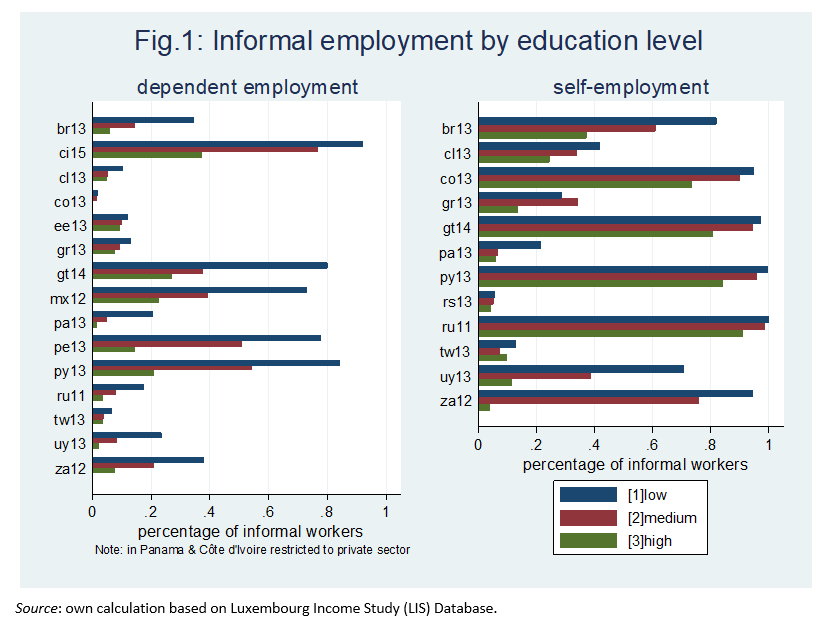

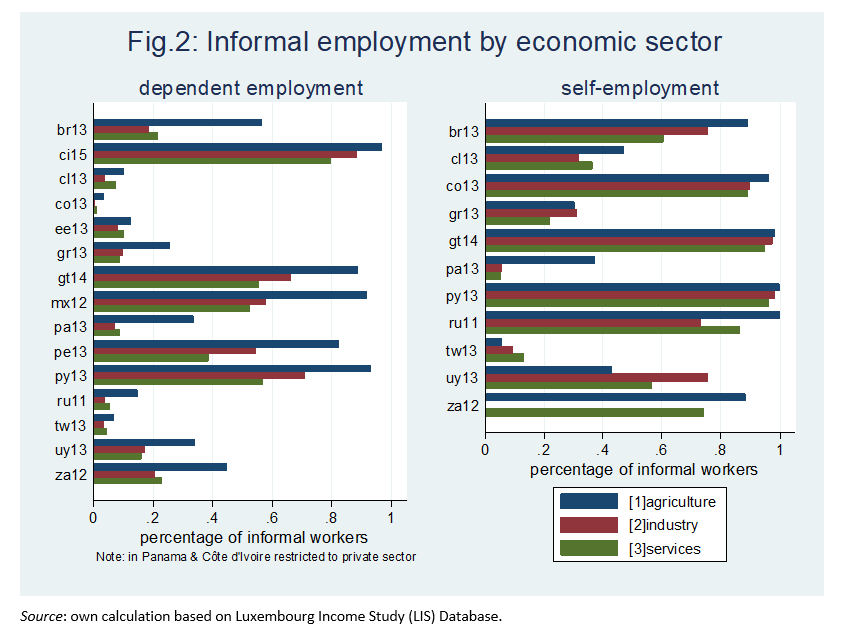

Figures 1 and 2 compile datasets for LIS Wave IX (around 2013), Russia 2011, and Côte d’Ivoire 2015, for all of which LIS has data concerning informal activities. A few countries were excluded from this overview due to the low relevance of informal activities (e.g. Luxembourg, Slovakia, and Estonia for the self-employed; in general, in Western Europe the labour legislation is stricter and consequently, the incidence of informal employment tends to be significantly lower).

Looking at informal employment by education level (see Fig. 1) we can see that among dependent employees, people with no education or lower than upper secondary level are more likely to be employed in the informal sector, with over 75 percent of them working in informal jobs in Côte d’Ivoire (96 percent), Guatemala, Peru, Paraguay, and Mexico. This pattern holds true for all countries, although there are conceptual differences in constructing the variable, as mentioned before. Nevertheless, care is needed when drawing conclusions about the magnitude of coverage of informal activities. Particularly striking is the low coverage of informal activities of dependent employees in Colombia, which relates to the problematic availability of appropriate survey questions to accurately capture informal activities (the question there refers to those who do not have any working contract, including a verbal one, while for other countries it refers to written contracts only). The group of the low-educated is followed by people with medium education and higher education, the highest frequency being in Côte d’Ivoire which has 71 percent of medium-educated and 40 percent of higher-educated people in the informal system. For the other countries the proportion of higher-educated people working in informal jobs is substantially lower.

However, the situation is not as diverse when we look at self-employment. It remains true that overall lower-educated people are more likely to be in the informal sector than medium- and higher-educated people. There is one exception – the case of Greece, where more people with a medium education level are in the informal sector (also because there are fewer people who do not at least have upper secondary education). In some countries the proportion of people with different education levels in informal self-employment is quite close (see Colombia, Guatemala, Paraguay, Russia), while in South Africa and Uruguay the proportion of highly educated people on the labour market is substantially lower.

Figure 2 looks at informal activities by economic sector. As expected, we can see that in most countries in the primary sector most jobs are informal, over 80 percent in the case of Côte d’Ivoire, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and Paraguay. For self-employment, the gap between the economic sectors is not that large, even very close in Colombia, Guatemala and Paraguay. In Greece and Uruguay most of the informal self-employment is observed in the industry sector, with 76 percent for Uruguay, while in Greece 38.5 percent of industry is informal. At the same time, in the service sector, more than half of all jobs in Côte d’Ivoire, Guatemala, Mexico and Paraguay are informal in nature, and so are those of the self-employed in Brazil, Colombia, Russia, Uruguay and South Africa. For Taiwan the service sector is the one with most informal jobs: 13 percent compared with 6 percent in agriculture.

What can be concluded from these conceptual differences and country-specific contents? First of all, understanding the different concepts of informal sector activities in different contexts is essential for comparative research. Second, however, the collected microdata does not always capture the full complexity of the informal labour market in different countries – hence users of the LIS and LWS databases need to carefully consider these differences when analysing informal activities across countries.

Being aware to the extent and complexity of the informal sector of the labour market is of utmost importance for policy makers that intend to design policies to reduce the informal sector. Some groups are more vulnerable than others to the informality of the labour market; for example, lower educated people, people working in agriculture and the self-employed, as we could see from the graphs presented. Although both facing similar risks of insecurity and lack of legal rights in the informal labour market, dependent employees and self-employed might need different targeted policies to improve their specific situation. In this regard, in its recommendation about the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy (ILO, 2017), the ILO draws attention to the necessity of implementing an integrated framework of policies ranging from pro-employment policies to policies that promote sustainable enterprises, accompanied by life-long learning aimed at improving the skills of lower educated people and their chances to enter the formal labour market sector.

References

| ILO at https://www.ilo.org. |

| Resolution concerning decent work and the informal economy, ILO, 2002, available online at https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/pr-25res.pdf. |

| Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy Recommendation, 2015 (No. 204) – Workers’ Guide, International Labour Office, Bureau for Workers’ Activities (ACTRAV), Geneva: ILO, 2017, available online at https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_dialogue/@actrav/documents/publication/wcms_545928.pdf. |