Issue, No.36 (December 2025)

Alimony received and paid: What is the impact on the risk of poverty after separation?

*

1. Introduction

Household dissolution may be harmful for separated parents and their children. Single-parent households face significantly higher poverty risks compared to two-parent families, highlighting the vulnerability associated with limited income sources and greater costs (Bradshaw et al., 2025). This trend is consistent across countries.

Alimony might be important to alleviate poverty risk after separation. The transfer of alimony for children (also known as child maintenance or child support) is based on the principle that both parents remain financially responsible for their child, even after separation or divorce. This transfer between households aims at redistributing income from non-custodial to custodial parents due to unequal caregiving roles or to minimise the income gap between the two post-separation households, ensuring that the child does not face a significant drop in living standards when moving between them.

Alimony has an impact on the available resources of both the parent who receives them and the parent who pays them and hence on their respective poverty risk and that of their children. This explorative paper uses the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) data to quantify this impact and to explore the role of alimony on the poverty risk after separation.

In terms of policy implications, this topic is essential to further study as child poverty has deep short-term as well as life-long consequences for children experiencing it (see among others De Schutter, Frazer, Guio and Marlier, 2023). It is therefore crucial to better understand the impact of family dissolution on the poverty risk of households and the potential need for additional public intervention to adequately support separated parents.

2. Data description

By “alimony”, we mean in this study both alimony directly paid by the ex-partner and public alimony paid by the public system when the defaulting parent failed to pay the maintenance as required. We are not able to differentiate between alimony paid to the ex-partner and the alimony paid for children both which are regrouped into a single variable.

It is largely documented that in many cases, alimony is not paid by the non-caring parent and that the alimony default payments are not effectively guaranteed by public authorities. It would therefore be worth to compare the situation of caring parents receiving and not receiving alimony and similarly for the non-caring parent. It is however difficult to perform such analysis with the LIS data, it is not possible to identify whether the household has children from a previous union. To estimate the impact of alimony on the poverty risk, we therefore select only households receiving/ paying alimony and compute their poverty rate with and without alimony.

Focusing on the sub-sample of alimony recipients (respectively of alimony payers), we measure the impact of alimony on the poverty risk, by comparing two poverty risk rates:

- One using the household disposable income (i.e., including alimony received and subtracting alimony paid) to compute the first poverty risk rate

- One using the “pre-alimony income” (i.e., excluding the amount of alimony received and including the amount of alimony paid) to compute a counterfactual poverty rate.

We are aware that this is a simplistic estimation, as we do not take into account the interplay between child support and social allowances (Olson, 2022). Indeed, in a number of countries, the income test to define the eligibility and amount of means-tested social allowances takes into account the amount of alimony received/ paid. It would also be interesting to take into account the interplay between child support payments and other social protection policies. In that case the poverty alleviation function of child support becomes ineffective (Hakovirta and Jokela, 2018; Hakovirta et al., 2020).

The poverty threshold is defined as 60% of the national median equivalised income1.

As we estimate the impact of alimony on different household types and as some concern only a small share of the population in some countries, we checked whether our computations were performed on minimal sub-samples, to ensure that findings are accurate, reliable, and meaningful, and not prone to random noise and large standard errors. A rule of thumb was to disregard sub-populations having 50 observations or less.

The household type available in the LIS data – variable typehh – uses the concept of dependent child, defined as a child aged 17 or younger, or a child aged 18 to 24 who is still in education.2

We selected the following countries for which there is available information on the alimony received and paid: Austria (2021), Belgium (2021), Denmark (2022), Finland (2016), Sweden (2021), and Luxembourg (2021). For details on the child maintenance system in these countries see, for instance, OECD (2024).

3. Distribution of alimony recipients and payers by household type

The following descriptive analyses explore the effect of the payment and the reception of alimony on the risk of poverty among people living in different household types.

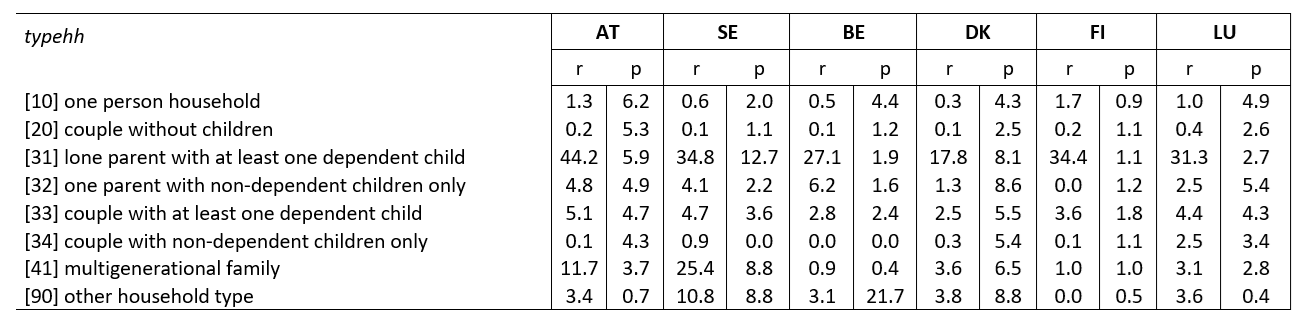

First, Table 1 reports the weighted proportions of individuals in each household type who receive or pay alimony and highlights the household types with the highest probability of being affected by the receipt or payment of alimony.

As expected, people living in households composed of a lone parent with at least one dependent child [household type 31] are proportionally more likely to receive alimony, however with sizeable cross-country variation.3 The percentage ranges from 17.8% in Denmark to 44.2% in Austria. Notably, Austria is also the country where the average amount received is comparatively higher as confirmed by the available evidence (Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto, 2022). Multigenerational family [41] and the residual category other household type [90] may be the next most likely to receive alimony, especially in Sweden (25.4% and 10.8%, respectively) and Austria (11.7% and 3.4%, respectively), although these results are less robust due to small sample sizes (see Table A2 in the Annex). People living in couples with at least one dependent child [33] constitute another group of alimony recipients. Although the proportion of recipients is lower in this group (ranging from 2.5% to 5.1%), this may represent a non-negligible number of people as a substantial share of the population lives in this household configuration (OECD, 2024).

Focusing now on alimony payers, they are represented across nearly all household types. Their share is relatively similar across all household types in Austria and Denmark (around 5%). In the other countries, the household type most concerned by alimony payments differs. In Belgium, people living alone are proportionally more likely to pay alimony (4.4%). The same holds in Luxembourg (4.9%), although lone parents (5.3%) and couples with dependent children (4.3%) are also concerned. Sweden stands apart, with lone parents the most likely to pay alimony (12.7%), followed by multigenerational and complex households (both around 8%). In Finland, the frequency of alimony payment is much lower, across all household types (around 1%). The probability of receiving and paying alimony may be influenced by the national legal rules, the sharing of responsibility and involvement between parents or the type of custody chosen. The latter varies a lot between the countries analysed in this paper, as shown by the data from the EU-SILC specific module on custody collected in 20214 : the proportion of children in shared custody after separation is the highest in Sweden (54%) and Denmark (41%), followed by Finland (33%) and Belgium (30%) and it is much lower in Austria (10%) (no available data for Luxembourg).

Table 1. Proportion of people living in household type receiving (r) or paying (p) alimony (%)

Note: r for receiving, p for paying.

Source: Authors’ elaborations by using LIS data

4. Impact of alimony on the poverty risk of people received or paying them

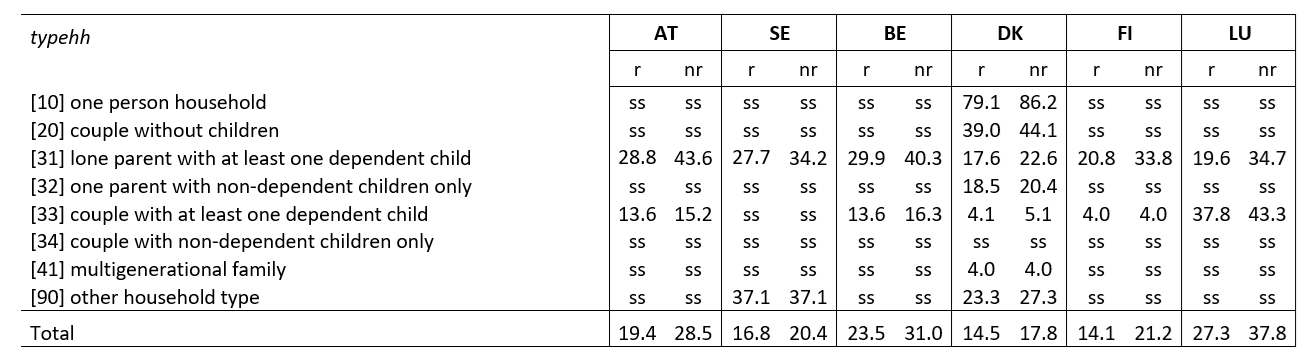

The effect of receiving alimony on the risk of poverty is shown in Table 2. The results show, that for the entire population of alimony recipients, the impact on the poverty rate varies across countries, ranging from 10 percentage points (pp) in Austria and Luxembourg to around 3 pp in Sweden and Denmark, with Belgium occupying an intermediate position (7 pp). These differences can be explained by the amount of alimony and the position of alimony recipients in the income distribution.

People in lone-parent households [31] are the most affected. If lone-parent households receiving alimony had not received it, their poverty rate would have increased by more than 10 pp in Austria, Belgium, Finland, and Luxembourg. For people in couples with dependent children [33] receiving alimony, the effect of non-receipt is negligible (even zero in Finland), with the partial exception of Luxembourg (-5.5 pp). This suggests that these households’ income lies sufficiently above the poverty threshold to remain unaffected by the simulated non-payment of alimony.

Table 2. Poverty rates by household type for the population receiving alimony only: income including vs. excluding alimony receipt (%)

Note: r for receiving, nr for not receiving; ss for low sample size (50 obs or lower)

Source: Authors’ elaborations by using LIS data

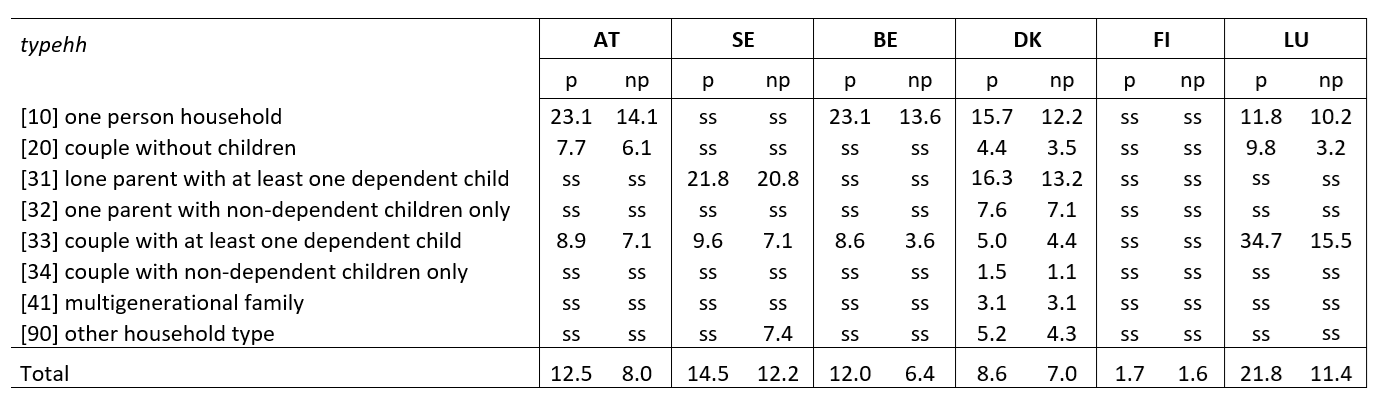

The effect of paying alimony on the poverty rate is reported in Table 3. The impact for the population of payers at the national level is the largest in Luxembourg (about 10 pp) and ranges between 2 pp and 5 pp in the other countries (no effect in Finland). Depending on the country, the sample is large enough to report results only for a few household types ([10], [20], [31], and [33]). In Finland, the sample of alimony payers is too small to show any results by household type.

The largest impact on the poverty rate is observed for alimony payers living alone [10] in Austria and Belgium (10 pp). In the other household types, the impact is lower (except in Luxembourg).

Table 3. poverty rates by household type for the population paying alimony only: income including vs. excluding alimony payment (%)

Note: p for paying, np for not paying; ss for low sample size (50 obs or lower)

Source: Authors’ elaborations by using LIS data

5. Conclusions and discussion

The paper presents very rough (mechanical) estimates of the impact of alimony on the poverty risk of people living in household receiving or paying them.

Overall, this descriptive exercise revealed alimony is crucial to reduce poverty among recipients, by up to 10 percentage points—especially for lone-parent households—while paying alimony can increase poverty risk for some payers (notably singles), the impact is much lower, with sizeable cross-country variation.

However, as previously explained, this analysis only focuses on alimony recipients and payers and thus omits the households not receiving/paying alimony but having children from previous unions. This therefore does not allow generalisation, as the latter may differ from the sample of those included in this analysis. Indeed, the determinants of whether a caring parent receives alimony (or spousal support) from the previous partner are influenced by a combination of legal, financial, and relational factors and are not randomly distributed (Cancian et al, 2025). The probability of receiving them is correlated with other determinants of poverty—such as education level, labour market attachment, and number of children—which makes it difficult to isolate the net effect of alimony on poverty risk. The same applies to households paying alimony. It would therefore be worthwhile to explore these interrelations further and to estimate the net effect of alimony once the usual poverty determinants are controlled for.

The data do not allow to know whether there is no alimony decided on between parents or whether the parent is in default of payment, whether there are other arrangements in terms of expenses sharing or family allowances sharing. Similarly, we have no data on the possible intervention of the public fund for alimony defaulting. However, it is well known that countries in which child support payments are guaranteed by the government perform much better in terms of securing the living standards of parents with the main custody, mothers in particular (Skinner & Hakovirta, 2020; Hakovirta et al. 2020).

This analysis also shows that better data are needed to better track the living conditions of children in separated families. It is important to clarify the rules governing inclusion of children living in multiple households in the sample survey. If the aim is to study the social, psychological and material living conditions of the children with separated parents, it makes sense to identify their living conditions in the different households to which they belong. Furthermore, this study is only based on household income. It would also be important to collect detailed data on expenses and cost sharing between the separated parents, as well as on family benefits sharing.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 Household incomes are ‘equivalized’ to render households of different composition comparable. We use the modified OECD equivalence scale which assigns a weight of 1 to the respondent, 0.5 to other persons over 13 years old in the household, and a weight of 0,3 to children below 14 years old.

2 typehh includes: [10] one person household; [20] couple without children; [31] lone parent with at least one dependent child; [32] lone parent with non-dependent children only; [33] couple with at least one dependent child; [34] couple with non-dependent children only; [41] multigenerational family; [90] other household type.

3 For completeness, Table A1 in the Appendix reports the weighted poverty rate by household type in each country, for those receiving, paying, and the overall population.

4 See Meyer et al., 2024.

References

| Bradshaw, J. R., Munalli, G., & Richardson, D. (2025). Comparing Child Poverty Using the Luxembourg Income Study and Policy Recommendations. Inequality Matters – LIS Newsletter, Issue 34, June 2025, Luxembourg Income Study. |

| Cancian, M., Costanzo, M. A., & Meyer, D. R. (2025). How important is formal child support for family economic well-being? Family Relations, 74(2), 891–900. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.13133 |

| De Schutter, O., Frazer, H., Guio, A.-C., & Marlier, E. (2023). The escape from poverty: Breaking the vicious cycles perpetuating disadvantage. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.51952/9781447370611 |

| Hakovirta, M., & Jokela, M. (2018). Contribution of child maintenance to lone mothers’ income in five countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 257-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717754295 |

| Hakovirta, M., & Mesiäislehto M. (2022). Lone mothers and child support receipt in 21 European countries. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 38(1), 36-56. https://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2021.15 |

| Hakovirta, M., Skinner, C., Hiilamo, H., & Jokela, M. (2020). Child poverty, child maintenance and interactions with social assistance benefits among lone parent families: A comparative analysis. Journal of Social Policy, 49(1), 19-39. |

| Meyer, D. R., Salin, M., Lindroos, E., & Hakovirta, M. (2024). Sharing Responsibilities for Children After Separation: A European Perspective. Family Transitions, 66(1–2), 27–55. OECD (2024). PF1.5 Child Maintenance (Child Support). OECD Family Database. Retrieved September 15, 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm |

| Olson, J. (2022). Interplay between child support and public assistance. Minnesota Department of Human Services. |

| Skinner, C., & Hakovirta, M. (2020). Separated families and child support policies in times of social change: A comparative analysis. In R. Nieuwenhuis & W. Van Lancker (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy, pp. 267-301. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_12 |

Appendix

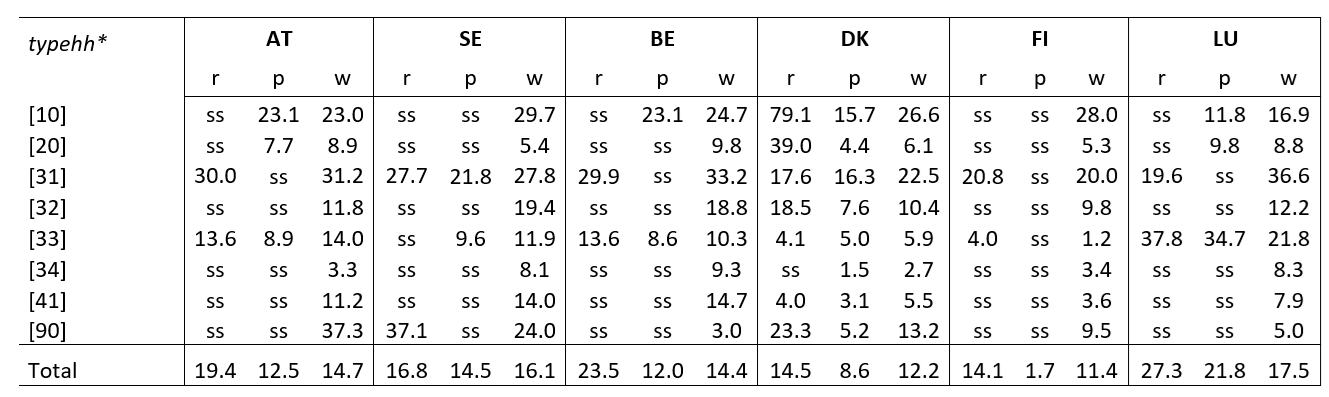

Table A1. Poverty rate by household type for those receiving and paying alimony and the whole population (%)

Note: * typehh includes: [10] one person household; [20] couple without children; [31] lone parent with at least one dependent child; [32] lone parent with non-dependent children only; [33] couple with at least one dependent child; [34] couple with non-dependent children only; [41] multigenerational family; [90] other household type.; r for receiving, p for paying; w for the whole population in each household type; ss for low sample size (50 obs or lower)

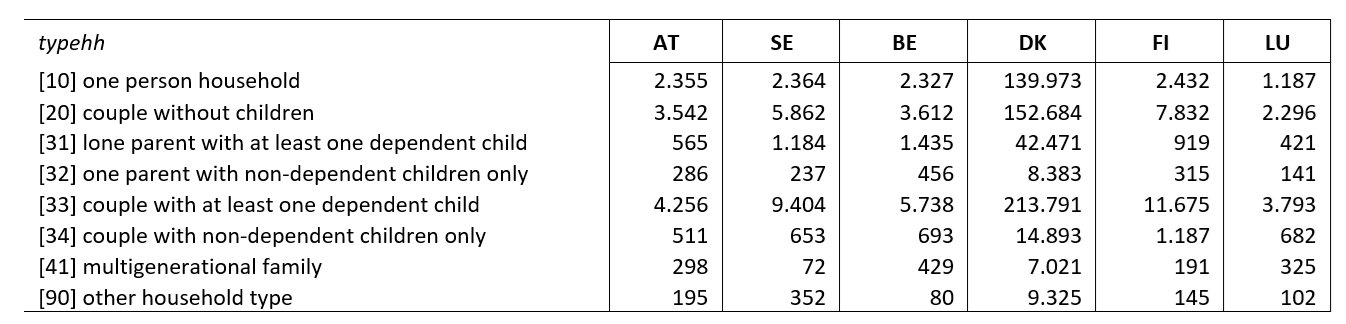

Table A2. (Unweighted) sample size of each household type in the total sample

Source: Authors’ elaborations by using LIS data