Issue, No.35 (September 2025)

In-Work Poverty, Social Protection, and Labor Market Institutions in Europe

1. Introduction

In-work poverty (IWP), defined as the condition of being employed while still facing a risk of poverty, has emerged as a persistent challenge in European societies. It reflects structural imbalances in labor markets, including the expansion of non-standard and low-paid employment, as well as the varying ability of welfare states to mitigate income inequalities. This underscores the well-established fact that employment and labour market participation alone cannot be considered reliable protective factors against the risk of poverty.

IWP is a complex phenomenon, encompassing both individual and household dimensions. It is defined by the employment status of individuals—typically workers employed for at least six months in a year—combined with the condition of living in a household at risk of poverty. Given this dual nature, addressing and reducing the incidence of IWP presents considerable challenges.

The existing literature mainly addresses the determinants of in-work poverty (Mussida and Sciulli, 2025) and discusses its definitions (Bavaro and Raitano, 2024). As for the drivers of IWP, both socio-demographic and household characteristics play a key role. Education, for instance, is generally associated with a lower risk of IWP, as it often corresponds to better employment conditions (Raitano et al., 2019). Conversely, being a migrant, having children in the household, or living with a household member with a disability may increase the risk due to less favorable employment conditions, lower work intensity, and limited access to public support (Ratti et al., 2022). The risk of IWP is particularly pronounced in single-earner households (Filandri and Struffolino, 2019). Despite holding disadvantaged positions in the labor market compared to men, women’s risk of in-work poverty is not necessarily higher. This is supported by previous studies (Broström and Jansson, 2023; Ponthieux, 2010, 2018; Ratti et al., 2022) and can be explained by the fact that employed women often serve as second earners within the household, a role generally associated with a lower risk of poverty.

Few studies highlight the role of institutions—such as social protection expenditure and labor market indicators—in potentially reducing the incidence of the phenomenon. In this regard, Eurofund 2017 and Hick and Marx 2022 demonstrated that labor market institutions—including employment protection legislation, union density, collective bargaining coverage, minimum wage laws, and active labor market policies—alongside social transfers, play a significant role in influencing the risk of IWP.

Some measurement issues are associated with the IWP indicator, including the definition of “in-work” individuals, whether to consider only employed persons or all labor market participants (both employed and unemployed), the sensitivity of the indicator to income changes, and how individual and household characteristics are combined, with some suggesting the use of household work intensity instead of individual months of employment (Mussida and Sciulli, 2025).

This contribution deepens the role of social protection expenditure and labor market characteristics in shaping the incidence and reduction of in-work poverty across 22 European countries1 over the period 2009–2023.

The impact of social protection expenditure on IWP is likely to vary according to its type and function: transfers aimed at reducing social exclusion and supporting the unemployed, for instance, are expected to have a more direct effect on lowering in-work poverty, whereas the total amount of social transfers – including both cash and in-kind benefits – may provide general income support but these are less directly targeted at in-work poverty. Regarding labor market characteristics, lower earnings inequality, a higher Kaitz index (indicating a stronger minimum wage relative to median earnings), and a lower rate of involuntary part-time employment are likely to be negatively associated with IWP by fostering more equitable and stable labor market conditions.

Drawing on the empirical findings, this contribution offers reflections for policy implications aimed at reducing in-work poverty and enabling employment to more effectively act as a mechanism of social inclusion.

2. Stylized facts

In-work poverty (IWP) has been rising in recent years across Europe. Table 1 reports the IWP rates for the European countries explored over the period 2009/2023. In 2023, 8.3% of EU workers aged 18–64 were affected by IWP.2 Despite its growing relevance, and although the European social policy agenda recognizes the importance of in-work poverty within the framework of the European Pillar of Social Rights, current levels indicate that IWP remains far from the targets set by the social pillar. Europe 2030 aims to achieve an employment rate of at least 78% among people aged 20–64, supported by strategies focused on creating more and better jobs—particularly in the green and digital sectors—promoting skills development and adult training, and fostering social inclusion and poverty reduction.

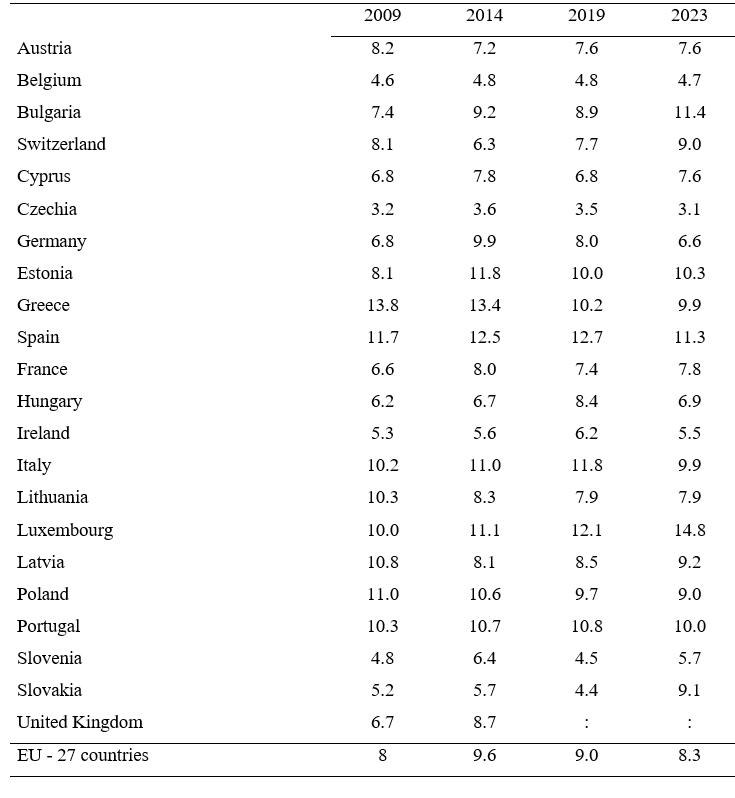

Table 1. In work at-risk-of-poverty rate (selected years)

Source: Eurostat.

From Table 1, we note that the IWP reflects the cross-country heterogeneity. The mentioned EU average for 2023 of 8.3% is the average of rates ranging from 4.7% in Belgium to 14.8% in Luxembourg. During the period, as well, there were different evolutions of the phenomenon in Europe. On the one hand, the IWP incidence increased significantly in Luxembourg, Bulgaria, and Slovakia (+4.8 percentage points, +4 percentage points, and +3.9 percentage points, respectively). On the other hand, there was a reduction, albeit to a relatively lesser extent, in Greece, Lithuania, and Poland.

Overall, the relevance of the IWP deserves an investigation of the possible factors reducing its incidence.

3. Empirical Application

3.1 Data

The application is based on a matched dataset for 22 EU countries and the period from 2009 to 2023. The In-Work Poverty (IWP) rate is determined using cross-sectional EU-SILC data, referring to the official definition first provided by Bardone and Guio (2005), described above. We relate the in-work poverty rates to several indicators of social protection expenses and labor market characteristics, as provided by the macroeconomic data of Eurostat and OECD. Particularly, we consider the total amount of social transfer (expressed in purchasing power standard per inhabitant), the amount distinguished into cash and in-kind transfers, and two specific functions strictly related to income and labor market conditions, i.e., social exclusion and unemployment. Related to the labor market, we focus on three key indicators: earnings inequality (measured by the 90-10 decile ratio of annual earnings), the Kaitz index (which represents the ratio between the median wage and the minimum wage), and the rate of involuntary part-time employment. Finally, we adjust the correlational analysis by weighting the results using Eurostat data on the employed population.

3.2 Results

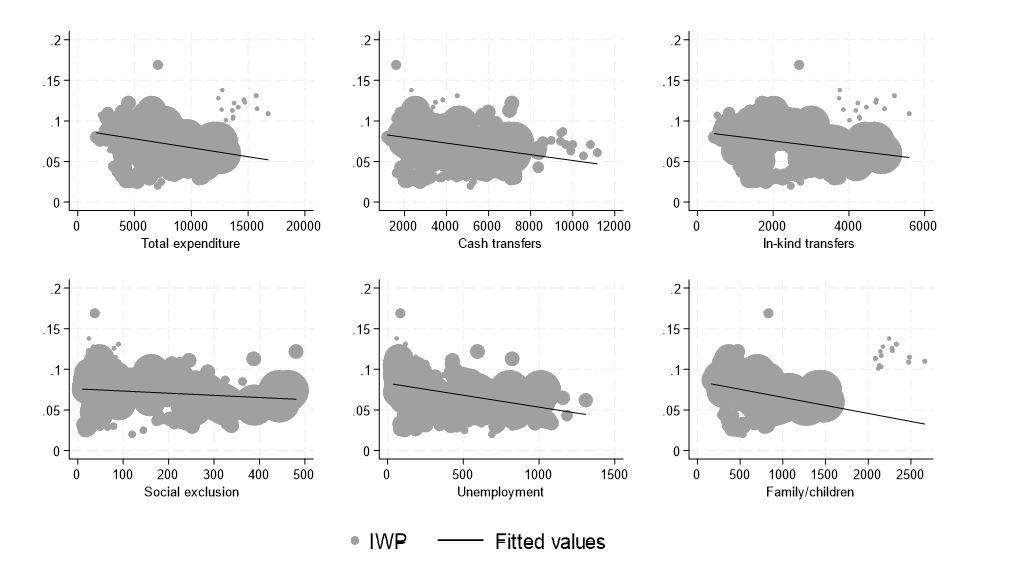

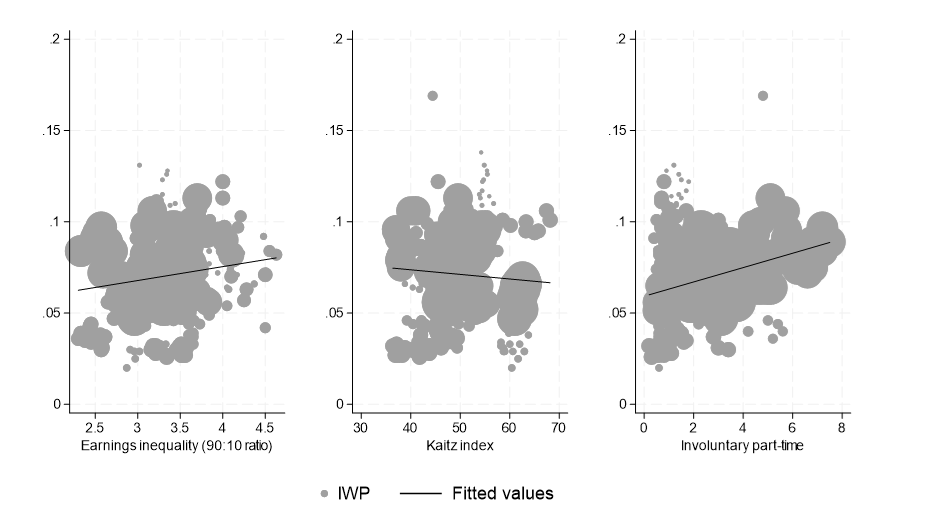

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the correlation over time between the IWP rate and the expenditure for social transfers and labor market characteristics, respectively. Graphs exploit the variability across countries and years in IWP rates and the mentioned indicators to uncover potential associations at the macro level.

In particular, Figure 1 shows that countries with higher social protection spending (especially in Nordic and Continental Western countries) tend to have lower IWP rates when compared to countries with weaker welfare systems.

Such an effect acts both via cash and in-kind transfers. They reduce in-work poverty by raising household disposable income and lowering necessary expenses. Monetary transfers offer immediate relief and directly contribute to income formation, thus reducing the risk that households fall below the poverty threshold. In-kind transfers, conversely, may provide a structural protection against poverty with positive long-term effects for IWP risk.

Focusing on different social protection functions, such as social exclusion, unemployment benefits, and family/children policies, reveals a greater effectiveness of the latter, especially compared to social exclusion expenditure. The support for family and children issues appears crucial, as the presence of children is a strong determinant of poverty risk at the household level. This stresses the importance of consistent design of social protection schemes, paying specific attention to weaker family groups. On the contrary, expenditure for social exclusion is less effective, possibly because smaller amounts are transferred, on average, to households. Finally, the expenditure for unemployment benefits is quite effective against the IWP risk, as it may prevent the transition from employment to unemployment of family members determines the fall into poverty.

All in all, the expenditure for social protection is relevant to fighting the IWP risk. Effective welfare systems are mainly targeted at working-age households and children, while maintaining incentives for employment.

Figure 1. In-Work Poverty incidence and the expenditure for social benefits

Note: The x-axis reports the amount (euros expressed in Purchasing Power Standard per inhabitant) spent for each of the indicators explored. The y-axis report the IWP rate. The lines show the effect of each indicator on the IWP rate over time, i.e. the 2009-2023 period.

Source: authors’ elaboration on EU-SILC, Eurostat, and OECD data.

Figure 2 illustrates the correlation between the IWP rate and three indicators of labor market conditions, including earnings inequality, minimum wage, and involuntary part-time employment.

Graphs show that higher earnings inequality is associated with higher IWP rates. The degree of inequality and the IWP incidence depend on the diffusion of low-pay and precarious jobs, and the effectiveness of labor market institutions affecting wage distribution, such as collective bargaining, trade unions, and minimum wage. The latter is directly investigated in the second graph of Figure 2, where the IWP rate is related to the Kaitz index, which measures the ratio between the nominal legal minimum wage and the median wage. The graph highlights the existence of a (slight) negative correlation, meaning that more generous minimum wage legislation may contrast earnings inequality and reduce the IWP risk.

In principle, one can expect that involuntary part-time work reduces both the level and stability of income, often locking workers into low-paid and insecure jobs. The third graph stresses this expectation, highlighting the existence of a positive correlation between the IWP rates and the diffusion of involuntary part-time. Fewer hours worked over the year lead to lower annual income and, then, a higher risk of poverty. Involuntary part-time is particularly widespread in low-wage economic sectors, thus exacerbating the negative consequences for household disposable income. It is also associated with limits in career progression, work insecurity, and fewer benefits, contributing to increasing the IWP risk in the long term.

Figure 2. In-Work Poverty incidence and labor market characteristics

Source: authors’ elaboration on EU-SILC, Eurostat, and OECD data.

In conclusion, the analysis stresses the crucial role of welfare systems and labor market characteristics and institutions play in the diffusion of the working poor. Their design and effectiveness, which may depend on the expenditure amount dedicated to each social protection function, determine important differences across countries in IWP rates. In policy terms, in-work benefits may be effective, as well as paying attention to the working-age population and children when designing the welfare systems. Reinforcing institutions capable of reducing earnings inequality, protecting workers from excessive part-time contracts and precarious jobs, and the enforcement of labor standards may be helpful.

1 The countries explored are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Cyprus, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Greece, Spain, France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Slovakia, and the UK. Data refer to the EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC).

2 Although the overall IWP rate is not extremely high, it is sensitive to fluctuations in the poverty threshold, which is conventionally set at 60% of median income; changes to this threshold can significantly alter the measured incidence of IWP (i.e. Lohmann and Marx, 2018).

References

| Bavaro, M. and Raitano, M. (2024). Is working enough to escape poverty? Evidence on low-paid workers in Italy. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 69: 495–511. |

| Broström, L. and Jansson, B. (2023). Who are the in-work poor? A study of the profile and income mobility among the in-work poor in Sweden from 1987 to 2016. Social Indicators Research, 165: 495–517. |

| Eurofound (2017). In-work poverty in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. |

| Filandri, M. and Struffolino, E. (2019). Individual and household in-work poverty in Europe: understanding the role of labor market characteristics. European Societies, 21(1):130–157. |

| Hick R. and Marx I. (2022). Poor workers in rich democracies: on the nature of in-work poverty and its relationship to labour market policies. IZA Discussion Paper No. 15163. IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn. |

| Lohmann, H. and Marx, I. (eds) (2018) Handbook onin-work poverty. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham/Northampton. |

| Mussida, C. and Sciulli, D. (2025). In-Work Poverty and COVID-19. In: Zimmermann, K.F. (ed) Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics. Springer, Cham. |

| Ponthieux, S. (2010). In-work poverty in the EU. Eurostat: methodologies and working papers. Eurostat, Luxembourg. |

| Ponthieux, S. (2018). Gender and in-work poverty. In: Handbook on in-work poverty. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham/Northampton. |

| Raitano, M.; Jessoula, M.; Pavolini, E.; Natili, M. (2019). ESPN thematic report on in-work poverty – Italy, European Social Policy Network (ESPN). European Commission, Brussels. |

| Ratti, L.; Garcia-Muñoz, A.; Vergnat, V. (2022). The challenge of defining, measuring, and overcoming in-work poverty in Europe: an introduction. In: Ratti, L. (ed) In-work poverty in Europe. Vulnerable and under-represented persons in a comparative perspective. Kluwer Law International BV, The Netherlands, pp. 7–8. |