Issue, No.34 (June 2025)

Occupational Assortative Mating and Gender Inequality in Earnings*

Introduction and Background

Assortative mating, or the tendency to partner with someone similar to oneself, has received considerable attention in the academic literature. This similarity among individuals could be conceptualized in diverse ways — education, occupation, or economic status (earnings, inherited wealth, for example). The literature has focused mainly on educational assortative mating and its implications for between-household inequality. Our research contributes to the literature by examining assortative mating in occupation and its association with gender inequality, emphasizing inter-household and intra-household earnings inequality.

With an increase in the age of marriage and more individuals entering the labour market before marriage, occupation as a mode for meeting potential spouses is likely to gain significance. Any change in patterns of occupational assortative mating is expected to have consequences for household earnings inequality.

However, evidence on trends in occupational assortative mating is minimal and based mainly on older periods (Hunt, 1940; Hout, 1982; Kalmijn, 1994). Most research on occupational assortative mating and inequality is limited to the U.S. and a few European countries (Schwartz et al., 2021; Frémeaux & Lefranc, 2020; Cheremukhin et al., 2023; Clark & Cummins, 2022). According to Schwartz et al., (2021), the prevalence of dual-professional couples in the U.S. in certain occupations has nearly tripled between 1970 and 2015-17 but most of the changes in occupational mating patterns are accounted for by changes in distributions of spouses’ occupations — particularly, the massive entry of women in the labour market and the rise of women in professional occupations. In contrast, studies from Europe suggest upward trends in occupational assortative mating. A study in France showed high levels of occupational assortative mating between 2004 and 2011 (Frémeaux & Lefranc, 2020). In England from 1754 to 2021, the degree of assortment by occupation was high (Clark & Cummins, 2022). Besides trends, some recent work on occupational assortative mating has examined its association with educational assortative mating and school-to-work linkages (Lopez-Rodríguez & Gutierrez, 2024; Han & Qian, 2021).

Everything else being equal, greater occupational assortative mating will increase inter-household inequality and decrease intra-household inequality. On the other hand, low occupational assortative mating would decrease inter-household inequality but could come at a cost of higher intra-household inequality, which is often disadvantageous for women (Lersch & Schunck, 2023). Thus, there is a tension between inter- and intra-household inequality. Studies have mainly considered the relationship between assortative mating and inter-household inequality. For example, Schwartz et al., (2021) find that the contribution of rising occupational assortative mating to economic inequality between households is small but higher than prior estimates of the effects of educational assortative mating on inequality.

We address this research gap in the following ways. First, we aim to paint a global macro picture of assortative mating in occupation for countries using LIS data spanning several decades to explore both spatial and temporal variation. Next, we explore how occupational assortative mating is associated with inter- and intra-household inequality in earnings (also referred to as between and within household earnings inequality, respectively). A global portrait linking assortative mating and household gender inequality will advance inequality research and praxis. Our research offers a new perspective on addressing economic inequality, a pressing concern globally.

Data and Methods

Our analysis is based on the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) global database that provides harmonized microdata over six decades across fifty-three countries. This article presents preliminary results for three countries – the United States, Germany, and Brazil.

Our analytic sample comprises heterosexual couple households where the head is living with a partner in a marriage, cohabiting, or in a consensual union. Our sample includes individuals aged 15-64 years, where both partners are employed. Employment can be in one of the three occupational categories – (i) Managers/Professionals (M/P), (ii) Other Skilled Workers (OSW), (iii) Labourers/Elementary (L/E). We rely on broad occupational categories as detailed occupations are available for fewer country-year datasets, limiting the scope of our global analysis. Moreover, broad categories keep this preliminary analysis simpler and easier to interpret.

We use the table-raking method to describe trends in occupational assortative mating (Schwartz et al. 2021). This method identifies the proportion of couples matched across the various occupational categories after accounting for changes in couples’ occupational distribution (by holding the marginal distributions of occupational categories constant at their earliest year values). Thus, after accounting for these changes, any increase/decrease in the proportion of matched couples can be interpreted as an increase/decrease in occupational assortative mating. To understand the relationship between assortative mating and intra-household earnings inequality, we use the wife’s share in couple earnings as an indicator for intra-household economic inequality (Malghan & Swaminathan, 2021).

Findings: Trends in Occupational Assortative Mating

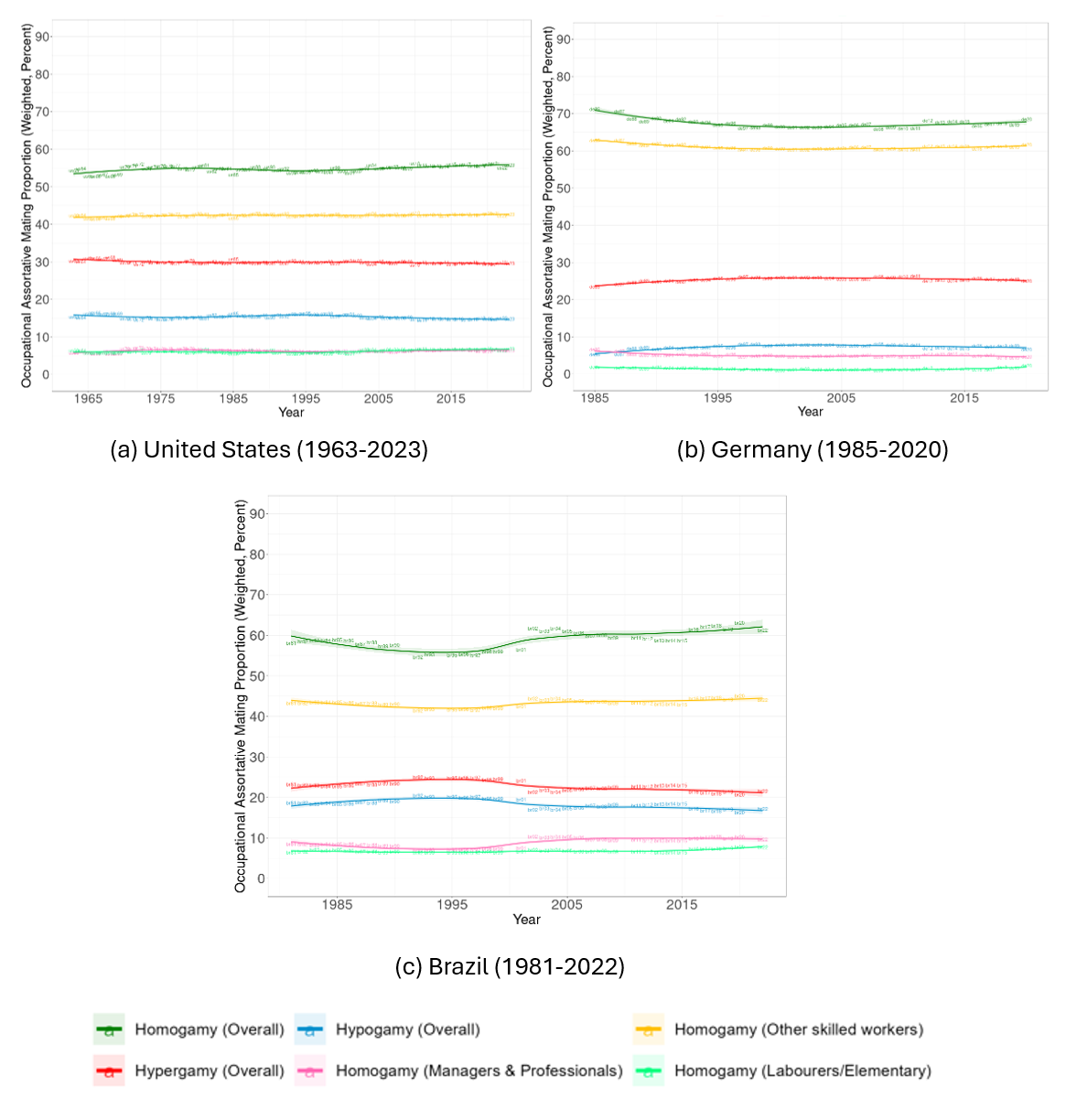

The proportion of couples matched on occupation (homogamy) across time for the three countries is presented in Figure 1. The figure also depicts the trends in occupational hypergamy (husband has an occupation level higher than wife) and hypogamy (wife has an occupation level higher than husband). The figure has been adjusted for changes in the occupational structure of the economy.

In the United States, over six decades, there has been a modest increase in occupational homogamy – from 54.3% in 1963 to 55.7% in 2023. Hypergamy and hypogamy trends have remained stable, with hypergamy being more prevalent than hypogamy throughout the period of analysis.

For Germany, there is a slight decline in occupational homogamy from 71.2% in 1985 to 68.5% in 2020. This decline is accompanied by a slight increase in hypergamy (23.5% to 25.0%) and hypogamy (5.2% to 6.6%).

In Brazil, the pattern of occupational homogamy resembles an S-shape, reflecting a decline from 58.1% in 1981 to around 54% in the early 1990s (1992-1996), followed by an increase to 61.3% by 2022. Consequently, trends in hypergamy and hypogamy show an increase during the same early 1990s period.

Analyzing the matched couples (homogamy), most occupational mating is among the other skilled workers category. In contrast, not more than 10% of the couples are matched in the managers/professionals and labourers/elementary occupations. This pattern is consistent across all three countries.

From Figure 1, it is evident that the three counties follow varying occupational matching trajectories. The United States shows a modest increase in homogamy, while Germany experiences a slight decline. Brazil’s pattern is more dynamic, with fluctuations over time. These trends suggest there may be multiple factors underlying these patterns, such as employment related laws and policies, cultural factors, and social norms.

Figure 1: Proportion of couples in the various mating categories over time

Findings: Occupational Assortative Mating and Intra-household Inequality

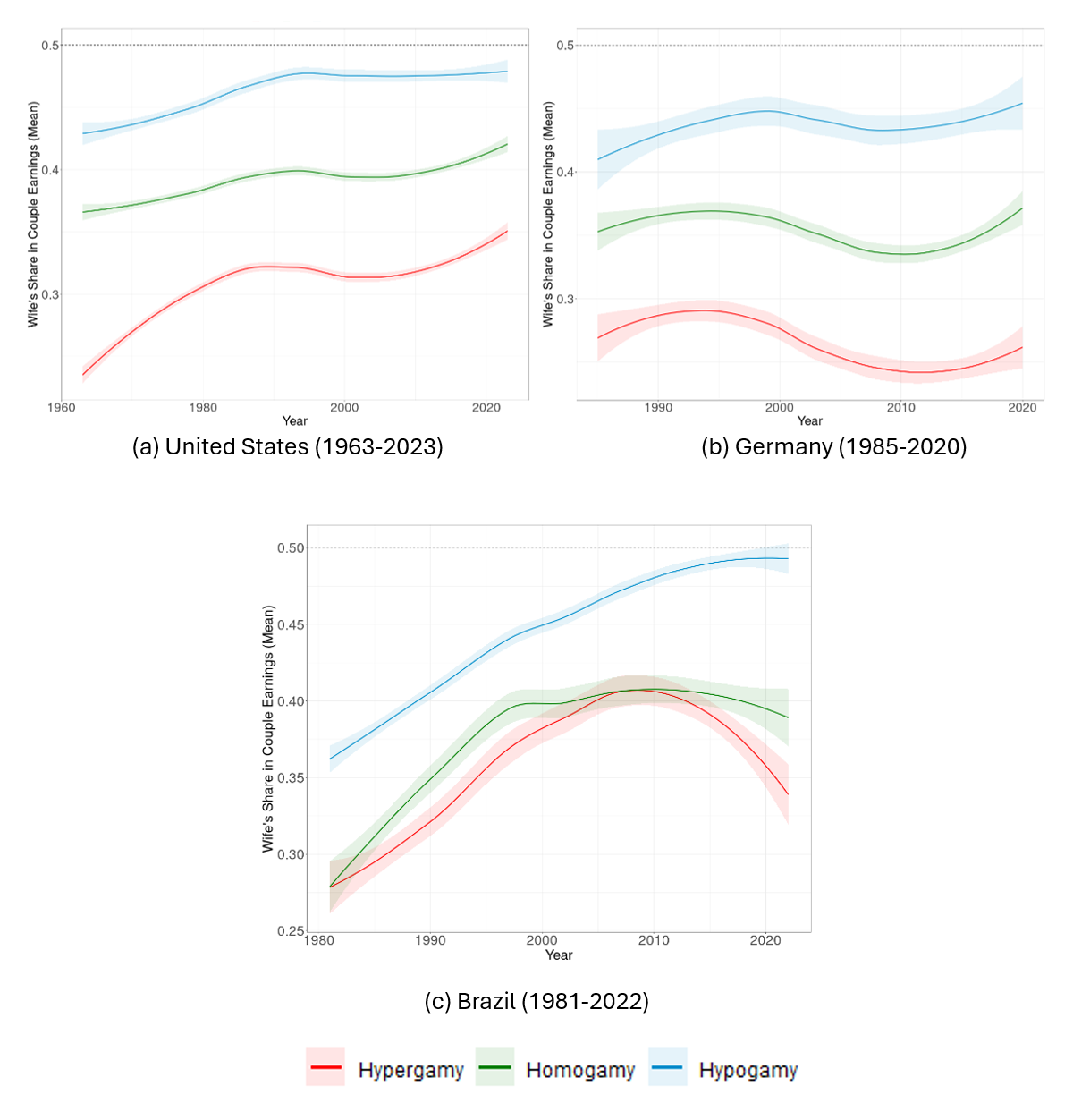

We analyze the relationship between occupational assortative mating and earnings inequality within the household. We plot the mean of the wife’s share in couple earnings for occupationally homogamous, hypergamous, and hypogamous couples (Figure 2).

For couples in the same occupation, the wife’s share is below 50% in all three countries, over the entire analysis period (see the dotted line at the 0.5 mark). Interestingly, even among couples where the woman’s occupational category is higher than the man’s, the wife’s share on average remains less than half. On the other hand, among occupational hypergamy couples, the wife’s share is much below the halfway mark, suggesting that the man’s share in earnings is greater than 50%. Thus, when couples are in the same occupation, and even when the wife is in a higher occupation, her earnings are not equal to the husband’s. This suggests that merely considering the extensive margin of work (where she participates in an occupation similar to the man’s) might not be sufficient to understand the earnings gap in occupationally homogamous couples. We must consider differences in work intensity (hours worked) and other factors, such as pay gaps within an occupational category, to understand the earnings gap within couples. Studies have shown that among individuals graduating from the same school and working in similar professional positions, there is a rise in gender gaps in earnings over time due to career interruptions and differences in hours worked (Bertrand et al., 2010). Evidence also suggests that there is a non-linear relationship between hours of work and earnings in certain occupations, such as in the corporate, financial, and legal fields. Hence, flexible working hours (often preferred by women after motherhood) come at a high cost (Goldin, 2014).

Figure 2: Mean of wife’s share in couple earnings over time

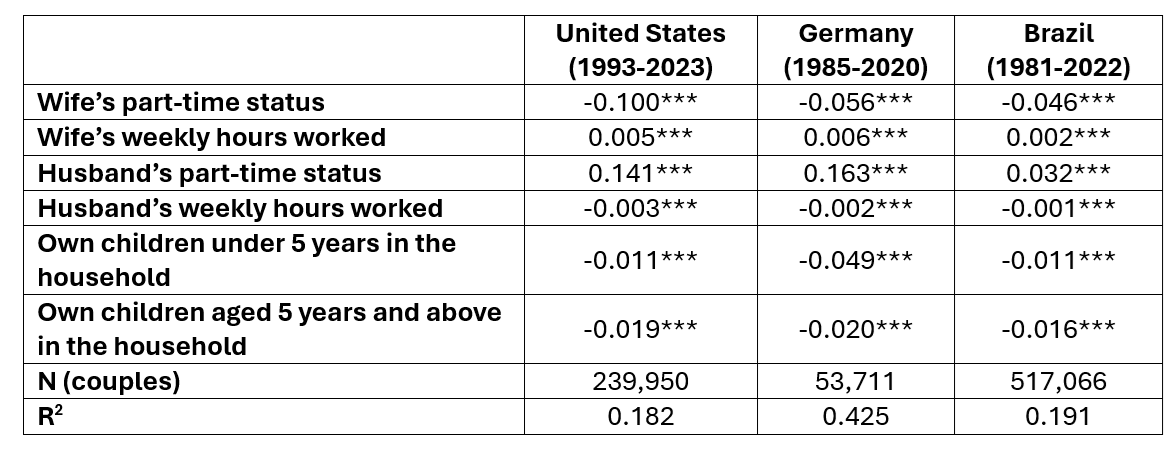

Therefore, for the occupation-matched couples, we examine the relationship between intra-household couple earnings inequality and factors capturing intensive work margin, such as weekly hours worked, type of employment (full-time or part-time), and the presence of children in the household. Results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 1.

: Pooled regression of wife’s share in couple earnings for occupationally matched – (homogamy) couples

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01

Note: Robust standard errors are in parentheses; all models include year-fixed effects.

After controlling for relevant factors such as woman’s education, age, occupation, and employment characteristics such as industry of the job (agriculture, industry, services) and sector of employment (public sector or private sector), we find that intensity of work matters among occupationally matched couples. An increase in wife’s weekly work hours is associated with a higher earnings share. On the other hand, her part-time work and the presence of children in the household are negatively associated with her earnings share.

Discussion

Our results show mixed trends in occupational assortative mating across countries, with modest changes over time. Among couples matched on occupation, the wife’s work intensity plays a vital role in driving differences in spouses’ earnings within the household. The decisions to work in jobs that require a certain number of hours or that are part-time might result from various factors, such as life cycle events like motherhood, the double burden of work, etc. We propose to expand our analysis to consider cultural and institutional factors that may be correlated with women’s employment and earnings. Likewise, analysis of detailed occupational categories and their attributes could shed additional light on the wife’s earnings share.

* This article is an outcome of a research visit carried out in the context of the (LIS)2ER initiative which received funding from the Luxembourg Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

1 Indian Institute of Management Bangalore

2 Asian Development Bank & Indian Institute of Management Bangalore

References

| Bertrand, M., Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2010). Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors. American economic journal: applied economics, 2(3), 228-255. |

| Cheremukhin, A. A., Restrepo-Echavarria, P., & Tutino, A. (2023). Marriage Market Sorting in the U.S. (No. 2023-023). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. |

| Clark, G., & Cummins, N. (2022). Assortative Mating and the Industrial Revolution: England, 1754-2021. |

| Frémeaux, N., & Lefranc, A. (2020). Assortative mating and earnings inequality in France. Review of Income and Wealth, 66(4), 757-783. |

| Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. American Economic Review, 104(4), 1091-1119. |

| Han, S., & Qian, Y. (2021). Concentration and dispersion: School-to-work linkages and their impact on occupational assortative mating. The Social Science Journal, 1-18. |

| Hout, M. (1982). The association between husbands’ and wives’ occupations in two-earner families. American Journal of Sociology, 88(2), 397-409. |

| Hunt, T. C. (1940). Occupational status and marriage selection. American Sociological Review, 5(4), 495-504. |

| Kalmijn, M. (1994). Assortative mating by cultural and economic occupational status. American Journal of Sociology, 100(2), 422-452. |

| Lersch, P. M., & Schunck, R. (2023). Assortative Mating and Wealth Inequalities Between and Within Households. Social Forces, 102(2), 454-474. |

| López-Rodríguez, F., & Gutiérrez, R. (2024). Social exchange or reinforcement of women’s educational advantage? The influence of educational assortative mating on occupational assortative mating for couples in Spain. International Sociology, 39(3), 241-260. |

| Malghan, D., & Swaminathan, H. (2021). Global trends in intra-household gender inequality. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 189, 515-546. |

| Schwartz, C. R., Wang, Y., & Mare, R. D. (2021). Opportunity and change in occupational assortative mating. Social Science Research, 99, 102600. |