Issue, No.24 (December 2022)

Three Tales of Gender Equality in a Post-Industrial World

Introduction

In recent decades, women’s economic independence has grown significantly due to higher levels of education, increased participation in the workforce, and a higher number of female-led households. In light of this reality, one might ask whether this increase in independence has been translated into a better economic position in society, and especially as women in developed economies still confront higher poverty rates, face persistent gender pay gaps, and are in a more vulnerable economic position than men. In addition, the benefits of economic independence may not be equally distributed among all women, and may vary depending on their position in the income distribution.

Extensive literature has covered the topic of women’s entrance into the labour market (Goldin, 2006; Esping-Andersen, 2009; Fernández, 2013), as well as the impact of female employment on income inequality (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2017) and household poverty (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2016). However, little is known about the overall effect of increased female labour force participation on women’s economic position, which is defined throughout this analysis as the disposable household income that women have access to.

Descriptive trends: women’s economic position has only increased for some

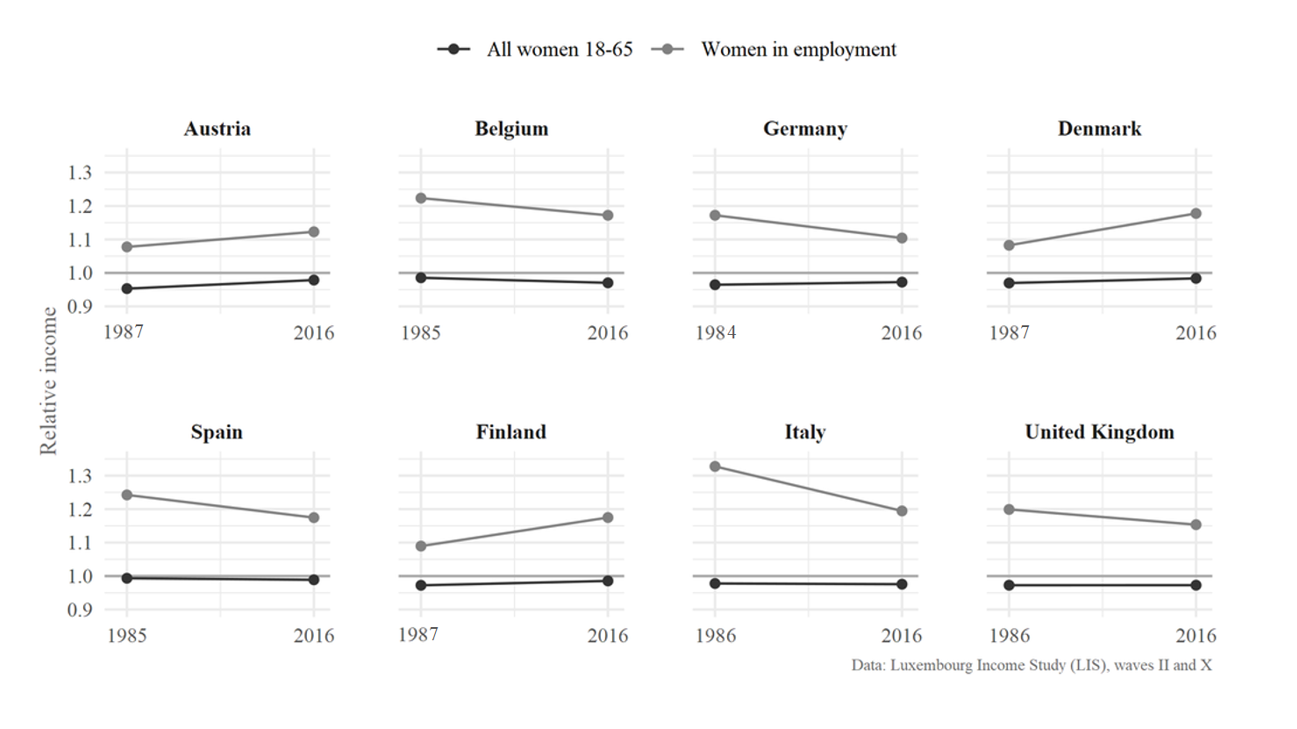

A first step to improve the understanding of the evolution in the economic position of women in the last few decades can be found in Figure 1. Here, the economic position of women is captured by relative disposable household income, a ratio between disposable household income equivalized by household size, and the average equivalised disposable income of the population at that point in time, so that the value for a person at the average will be 1. This measure provides a way to compare the economic position of women to the average across the population.

Using a relative measure of income has two essential advantages. First, it makes individuals comparable in a context of important geographical and country variation, minimising the noise coming from different economic contexts. Second, it manages to capture women’s economic position in relation to the rest of the population, providing information both on living standards and on the spread of the income distribution. In addition, the analysis focuses on household instead of individual income, to account for the fact that individual income is commonly complemented (or complements) the income of other household members. In this line, despite the measurement limitations of household income as an indicator of economic wellbeing, such as the fact that income may not be shared equally across household members, it can still be considered as the best indicator one can have of economic wellbeing when compared to other alternatives (Canberra Group, 2011).

This article uses data from the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database. LIS data offers standardised income and socio-economic data for a large sample of developed economies and is the income database that allows to cross-nationally compare countries further back in time. The analysis looks at eight Western European countries which cover the four welfare state regimes: Nordic (Denmark and Finland), Continental (Austria, Germany and Belgium), Anglo-Saxon (United Kingdom) and Southern (Spain and Italy). Data comes from waves II (around 1985) and wave X (2016).

Figure 1. Economic position of all women and women in employment

Overall, despite increased economic independence, women as a group show minimal variation in the evolution of their economic position compared to the average of the population, with the economic position of working-age women not having changed significantly since the 1980s. The relative disposable household income of women is consistently below the average for the population, although it is close to the mean. There are some cross-country differences, with modest improvements in Austria, Denmark, and Finland. However, on average, it does not appear that increased labour force participation has had a strong effect on women’s relative household income. For employed women, the relative (equivalised) household income shows more variation across countries. Again, only Austria, Denmark, and Finland have seen an increase, while in other countries, working women’s relative household income is lower than it was in the 1980s.

There are a number of explanations for these trends that can be derived from the literature. First, they can be related to overall trends in the labour market, including the fact that careers have become less stable, and male earnings have declined (Binder and Bound, 2019; Juhn, 1992; Moffitt, 2012; Abraham and Kearney, 2020). Secondly, women still face important barriers in the labour market, such as persistent gender pay gaps, vertical and horizontal segregation into less paid positions or high rates of precarity (Sigle-Rushton and Waldfogel, 2007; Goldin, 2014; Blau and Kahn, 2017).

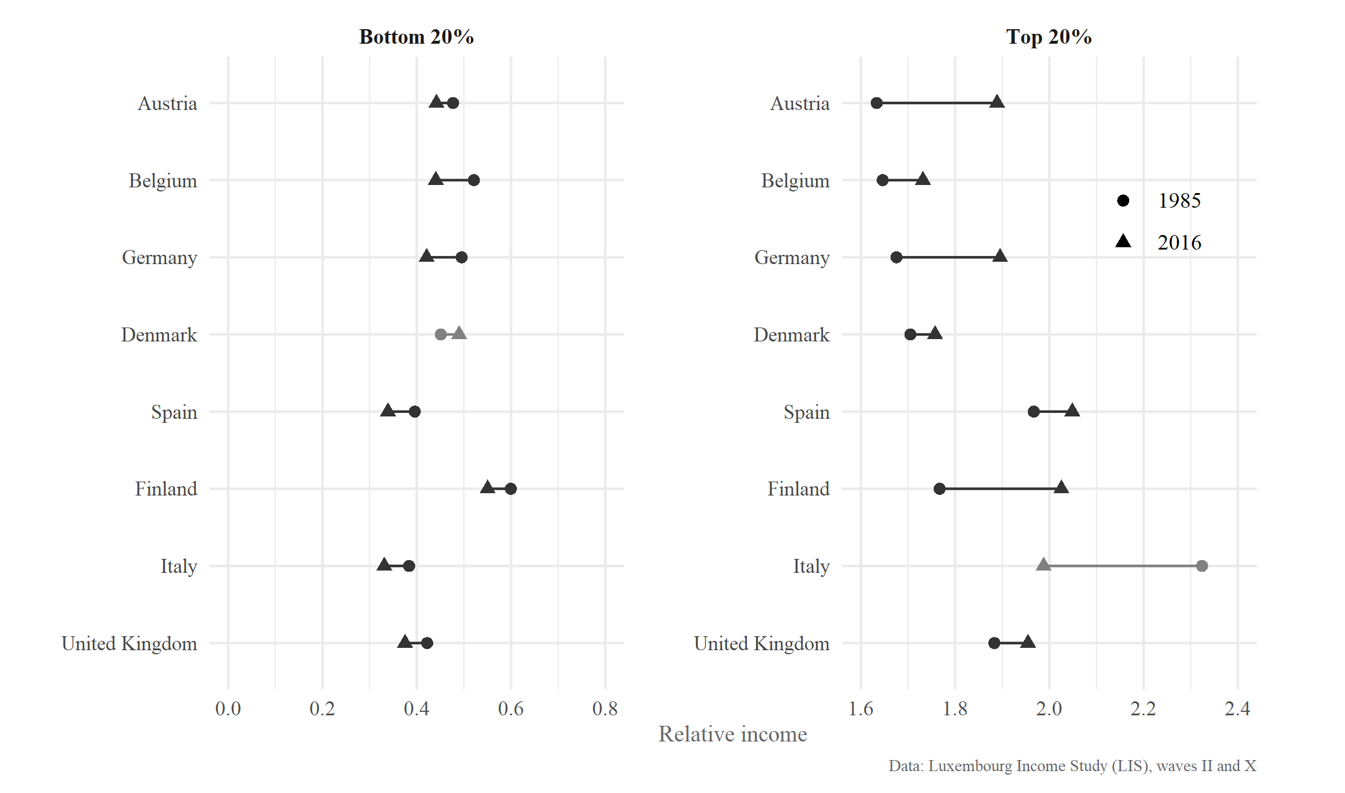

But what happens when shifting the analysis away from the average female? Figure 2 breaks down the changes in relative (equivalised) household income of women to focus on the bottom and top 20% of the income distribution between 1985 and 2016. A first look at the data suggests that the apparent stability seen in Figure 1 hides significant variation among women. While the living standards of the women at the top 20% of the income distribution have increased, those of women at the bottom have gone down, suggesting that overall stillness hides an increase in inequality.

Figure 2. Economic position of women across the income distribution

The data indicate that women at the bottom 20% of the income distribution have seen a decline in their economic position in all countries except Denmark. In contrast, women at the top 20% of the income distribution have generally improved their position, with the exception of Italy (country specific trends are further discussed in the working paper). This opposing evolution in economic positions followed by women at different extremes of the income distribution can be seen as an indicator of the emergence of winners and losers of the economic independence among women.

The role of changing family structures

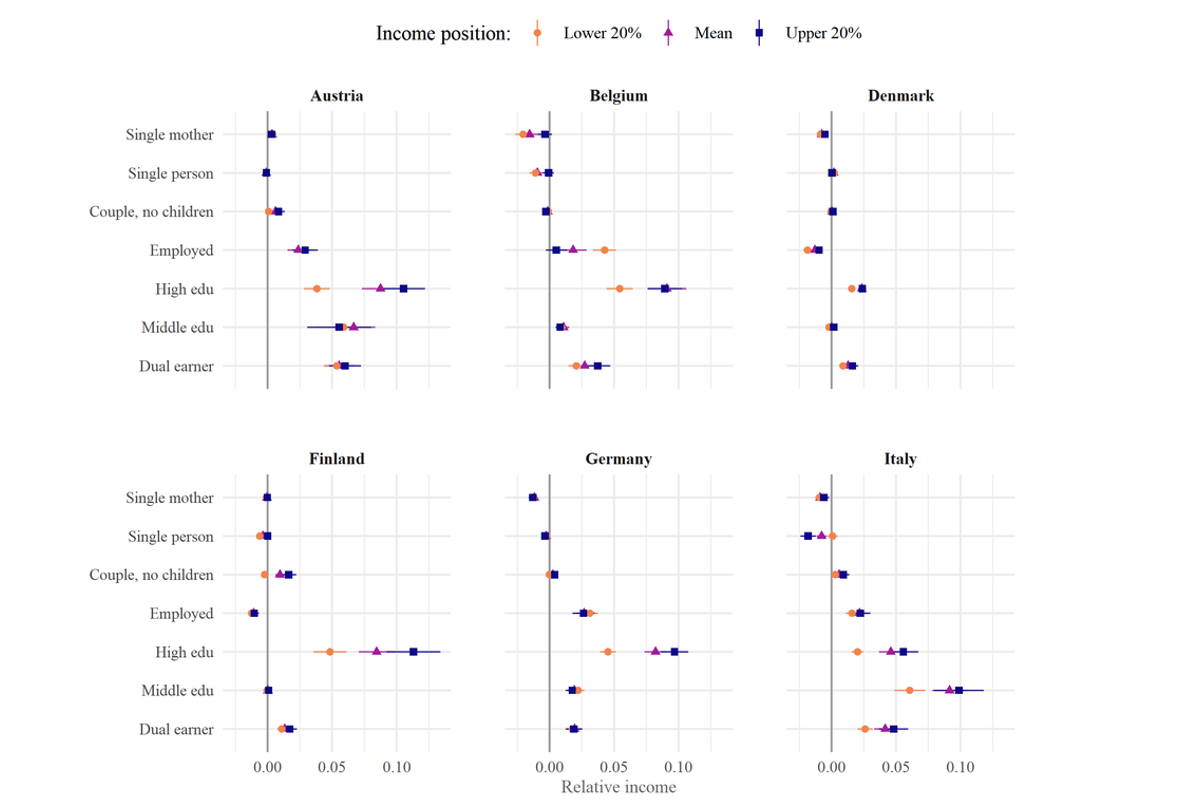

What explains the divergent trends in the economic position of women at the different ends of the income distribution? To answer this question, the next step of the analysis uses a RIF regression approach to Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Firpo et al., 2009; Oaxaca, 1973). This approach compares each country with itself in the past, looking at the mean, the 20th, and the 80th percentiles of the income distribution. In essence, using a decomposition approach allows us to determine which changes in women’s economic position are due to changes in the composition of the group (such as increased employment and higher education or changing family structures) and which are due to changes in the effect of specific variables (for example, the effect of employment on relative (eq.) household income may differ in the 1980s than in 2016).

Figure 3 shows the “endowment” effects of the decomposition, this is, the changes explained by changes in the composition of the group, broken down by predictor variables. It should be noted that the effects of family types should be read as a difference from the baseline category, which is, in this case, low educated women with children out of employment living in male breadwinner family structures.

Figure 3: RIF decomposition endowment effects

Two main points can be derived from this figure. First, the results show a positive effect of employment in all countries except the Nordic countries. This is likely because female employment was already high in Finland and Denmark in the 1980s, so the data indicate that women are better off in terms of relative income when they have higher employment rates. Second, the results also highlight the importance of family structures for women’s economic position. In five out of six countries, the increase in the share of single mothers has made women worse off. At the same time, the increasing share of dual-earner families has improved the relative position of women in all countries. However, these family structures are not evenly distributed across the income distribution. Single mothers are concentrated at the bottom of the distribution, with 45% at risk of poverty in the EU (Eurostat, 2018), while dual-earner families generally fare better than other types of households in developed countries (Nieuwenhuis et al., 2016). The analysis suggests that changes in family structures are having a disequalising effect among women and may be a reason for the decline in the economic position of women at the bottom of the income distribution in recent decades.

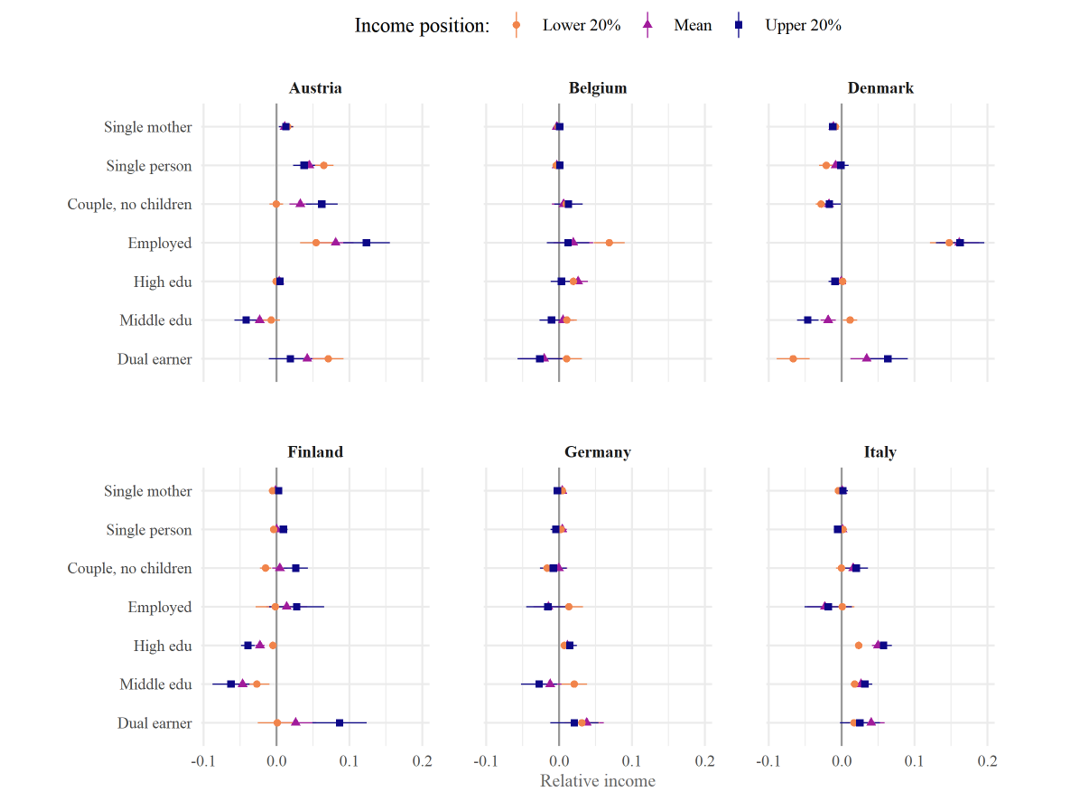

As a last step in the analysis, Figure 4 shows the “coefficient” effects of the decomposition, that refer to the degree to which the effects of the independent variables have significantly changed from the 1980s to 2016.

Figure 4: RIF decomposition coefficient effects

Although not shown in the figure due to large differences with other effects, it is important to note the role of the intercept, which has a negative sign in all countries (see the working paper). This means that male breadwinner families are worse off today than they were in the 1980s, and that effects that appear to be zero in the figure also have negative outcomes for women when the intercept is taken into account. This is the case for the single mother category, which is close to zero in all countries, but has a negative change in effect when added to the intercept.

Overall, it seems that what is hindering the translation of increased economic independence into higher living standards is the negative impact of certain family structures on women’s economic position. This is seen in the negative change in coefficients for being part of a single mother, male breadwinner, or single earner household in all countries. Once again, this suggests that economic emancipation may have different effects for women depending on the type of family they live in and their position in the income distribution.

Concluding remarks

The main goal of this analysis has been to show that economic independence has had a very different effect on women depending on their position at the income distribution. In particular, the results just presented show the emergence of three different stories. A story of emancipation for women at the top 20% of the income distribution, who have seen an increase in their living standards during the last decades. A story of compensation for women at the middle of the distribution, who manage to compensate with their household income. And a story of undelivered promises for women at the bottom 20%, who, despite increasing economic independence, have seen a deterioration of their living standards.

The decomposition analysis shows that both employment and higher education levels entail an improvement in women’s economic position. However, the effect of this relationship is mediated by changing family structures that create winners and losers. Notably, economic independence seems to ameliorate the relative position of women in dual-earner couples while worsening the living standards of single mothers. The unequal distribution of these family structures across the income distribution raises important concerns for inequality among women.

The relevance of this analysis is twofold. First, it has shown that despite the increase in female labour force participation, women as a group have not seen an improvement in their economic position in society, as measured by disposable household income. Second, it has shown the importance of going beyond aggregate indicators, as the apparent stability of living standards hides important differences among women depending on the extreme of the income distribution a woman belongs to.

From a policy perspective, results highlight the need to take a multidimensional approach to social policy design. While the overall income position of women has remained relatively stable from the 1980s, women who are part of specific groups such as low-skilled workers, working mothers, single mothers or low educated women may require more targeted policy action.

References