Issue, No.19 (September 2021)

Work-Family Reconciliation Policies: Good or Bad for Gender Employment Inequalities?

Introduction

In the work-family policy literature a debate persists about whether generous work-family reconciliation policies (those that help parents, mainly mothers, reconcile tensions between paid and unpaid childrearing, such as leave and early childhood education and care (ECEC)) promotes women’s employment, but have adverse consequences for women’s attainment. Key to this debate is a growing consensus that these policies may differentially impact women’s employment and attainment, by class. Many researchers in this genre utilize policy indicators (hereafter, indicators) in combination with the LIS data to evaluate the links between these policies and women’s outcomes (Mandel and Semyonov 2005, 2006; Pettit and Hook 2009; Mandel 2012; Korpi, Ferrarini and Englund 2013; Brady, Blome, and Kmec 2020).

In this article I extend this research. I first address the call for better indicators (Hook and Li 2020; Mandel 2012; Sirén et al. 2020). I present seven new, disaggregated, precise, and multidimensional indicators for leave and ECEC across 24 high-income countries and relationships among the indicators (These indicators are available in a new policy dataset along with detailed documentation here). I then evaluate the relationships between the policy dimensions and gender gaps in employment and annual earnings (hereafter, earnings) for working-aged low-and highly educated men and women using the new indicators and the LIS data for 24 high-income countries around the years 2010 and 2013 (Waves VIII and IX). The goal is to evaluate both parts of the gendered tradeoffs hypothesis (links with employment and attainment) for the two class groups. I do this by using established methods from the literature and the new indicators, to determine relationships among the policy dimensions and outcomes of interest.

“Well-developed” work family reconciliation policies

Leave and ECEC policies are the two most widely studied work-family reconciliation policies in the research on the unintended consequences of family policies (Hook and Li 2020). Though both policies help mothers reconcile work with unpaid childrearing, the policies have different implications for women’s attainment – leave promotes mothers’ exit from the labor market for one or more periods of time and may negatively affect earnings and status, while ECEC promotes women’s time at work and should not be linked with adverse outcomes. Many of the indicators used in past studies are overly simplified, do not include periods of leave for fathers’ use, and include only one indicator of leave and ECEC.1

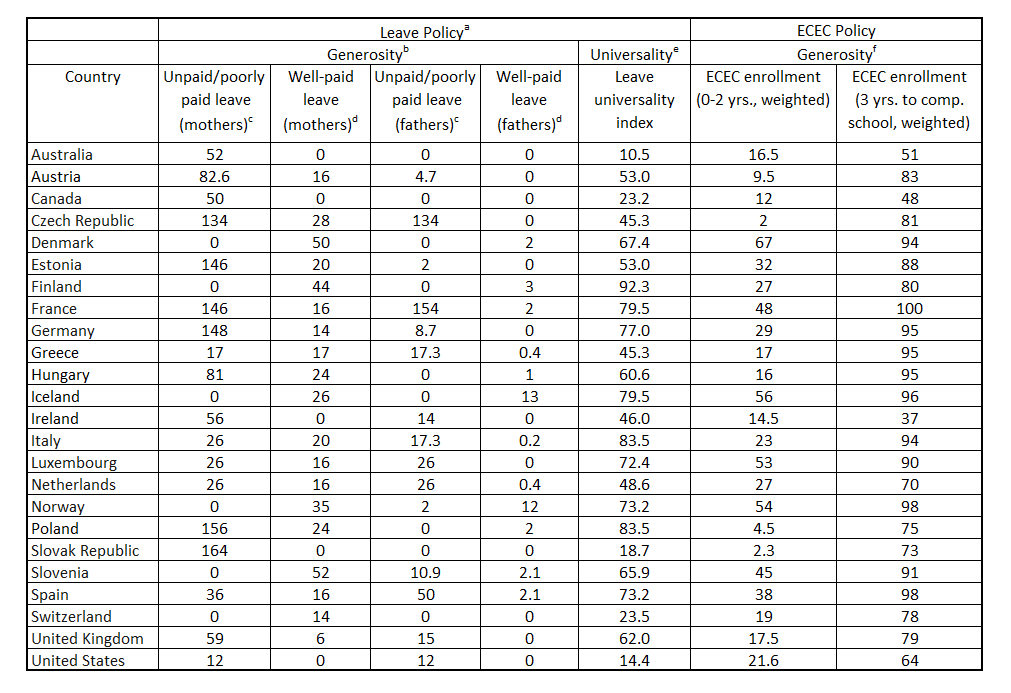

Table 1. Leave and ECEC policy dimension indicators for 24 high-income countries

Notes: Countries for which policy data comes from around the year 2009/2010: Australia, Canada, France, Iceland, Ireland, the Slovak Republic. All other countries’ policy data is from around the years 2011/2012/2013. For detailed methods of indicator construction, see the documentation for the Leave and ECEC policy dimensions dataset for 31 high- and middle-income countries.

aLeave policy includes maternity leave, paternity leave, and parental leave (where applicable).

b Indicators measure “how much” leave is available in leave legislation. Reserved (transferrable + nontransferable) + shared leave periods (including any mandatory or optional weeks of pre-birth leave) are included in the two indicators for leave allocated to mothers. Reserved and nontransferable leave periods only are included in the two measures for leave allocated to fathers.

cUnpaid/poorly paid leave = leave paid at less than 67 percent of usual earnings or unpaid.

dWell-paid leave = leave paid at 67 percent of usual earnings or higher.

eThe leave universality index was calculated using the multiplicative method and converted to an index with a range between 0-100. The higher the value, the more universal the leave policy legislation in any particular country. The index is constructed using five separate indicators of leave universality: maternity leave coverage, leave financing of paid leave periods, and leave eligibility requirements. For the financing of leave and leave eligibility requirements, both dimensions are measured for leave allocated to mothers and fathers.

ECEC generosity indicators measures the availability of care (childcare services and pre-primary education) for young children in two groups.

fWeights for the provision of care as followed: public care = 1 (enrollment rate remains the same), mixed provision = .75, and private care = .50.

Sources: Author’s own calculations using various sources; for detailed source information and full bibliographic entries, see the documentation for the Leave and ECEC policy dimensions dataset.

I propose seven new indicators, five for leave and two for ECEC, that measure different policy dimensions (see table 1). The seven new indicators show which policies are “well-developed”; those policies that best support women’s employment across multiple policy dimensions, based on evidence from earlier scientific studies (Gornick and Meyers 2009; Kostecki 2021).2 Four of the leave policy indicators measure generosity or “how much” leave is reserved for the mothers’ and fathers’ use. The index of leave policy universality measures “the breadth of the population covered under leave legislation as well as the accessibility of leave.” For ECEC, two indicators measure ECEC availability; young children’s enrollment in childcare services (between 0 and up to 2 years) and slightly older children’s enrollment in pre-primary education services (between 3 years and up to compulsory schooling), weighted by the dominant mechanism of provision (public or private care).

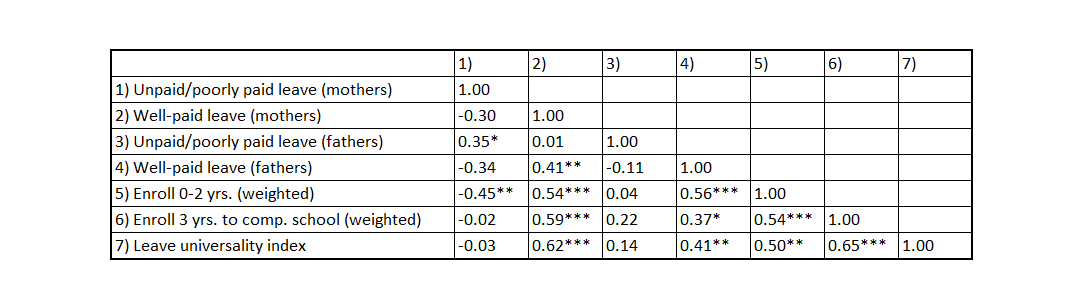

Table 2. Correlations among the seven leave and ECEC policy dimension indicators from Table 1

Notes: Pearson correlation coefficients.

Source: Author’s own calculations using Stata statistical software and values for the seven policy indicators shown in Table 1.

*P< .10, **P< .05, *** P< .01.

Relationships among the indicators are shown in Table 2 using Pearson correlation coefficients. The correlation results generally show the policy dimensions are positively and significantly correlated with one another, suggesting leave and ECEC policies that are well-developed along one dimension are well-developed across other dimensions. The exception are the correlations among the unpaid/poorly paid leave indicators and additional indicators. These policy dimensions are generous in terms of length, but not payment, which suggests unpaid/poorly paid leaves may not be “well-developed” in comparison to other leave and ECEC policy dimensions. Long, unpaid/poorly paid leave periods are also negatively and significantly correlated with enrollment of children 0-2 years of age (because mothers stay home to care for children). Overall, the correlations show the importance of measuring leave periods (for both mothers and fathers) at different wage replacement cutoffs.3 More precise indicators of leave policy especially complicate the issue of how to measure these policies for use in comparative research.

Leave, ECEC and gender gaps: employment and annual earnings

This section assesses the links among the policy dimensions and gender gaps between men and women across measures of employment and annual earnings using correlation analyses and multilevel modelling. The sample is of men and women 25-54 years of age (prime working-aged persons that excludes students and early retirees). The focus is on gender gaps in employment and earnings between low-educated men and women (below a high school education) and highly educated men and women (at least a tertiary education or higher).4 Education is used as the measure of class. Education is an indicator of skill and harmonized by LIS for comparative research. Earnings is a measure that is a widely used measuring women’s attainment.

The methods for the multilevel model analyses were adapted from Mandel (2012) and Brady, Blome, and Kmec (2020). All 24 countries are included in the employment models. The sample is reduced to 18 countries for the earnings models to exclude countries that report net or mixed earnings5 and where weekly hours worked cannot be used as a control variable.6 Earnings were first converted to country-year specific percentiles.7 The same countries are included in the correlation and multilevel analyses.

The questions are whether well-developed leave and ECEC policy dimensions are linked to reduced gender gaps in employment, but unintended, wider earnings gaps between men and women? Do these relationships differ across class groups?

Correlations

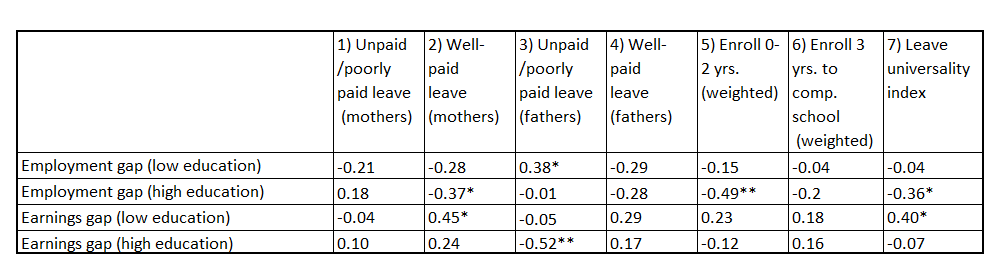

Table 3 displays Pearson correlation coefficients among the seven policy dimensions and the two outcomes for the two class groups. A negative correlation implies the policy dimension is correlated with smaller employment or earnings gaps. Positive correlations signal the policy dimension is correlated with wider employment or earnings gaps. Positive correlations therefore imply the unintended consequences of leave or ECEC policy.

Table 3. Correlations among the seven leave and ECEC policy dimension indicators and gender gaps, employment and annual earnings, low- and highly educated men and women

Notes: Sample includes men and women aged 25-54 years. Pearson correlation coefficients. Countries included in the correlations are the same countries included in the multilevel models. Gaps are unadjusted.

N=24 countries (employment gaps). For the correlations between unpaid/poorly paid leave for fathers and employment gaps, the Czech Republic and France were removed because the leave values had too much an influence on the results (N=22 countries).

N=18 countries (annual earnings). Only those countries with reported gross earnings and hours worked in the LIS data are included in the correlations and multilevel models. In addition, the Czech Republic is removed from the correlations between unpaid/poorly paid leave (fathers) and earnings gaps because the leave value has too much of an influence on the results (N=17 countries).

Source: Author’s own calculations using Stata statistical software and values for the seven policy indicators shown in Table 1 and the LIS data Waves VIII and IX.

*P<.10, **P <.05, *** P < .01.

The correlation results suggest that different leave and ECEC policy dimensions may have different relationships to women’s employment and attainment and that these relationships vary by class. There are no unintended relationships among the policy dimensions and outcomes between highly educated men and women. Any unintended relationships among the policy dimensions and outcomes are for the low-educated group. Unpaid/poorly paid leaves for fathers are moderately and positively correlated with the employment gap between low-educated men and women. Well-paid leaves for mothers and the universality of leave are moderately and positively correlated with earnings gaps between low-educated men and women. The results again point to the importance of measuring leave allocated to both mothers and fathers at different wage cutoffs.

Multilevel models

Supporting the correlation results, a one percentage point increase on the universality index improves highly educated women’s employment odds by .007, holding the other variables constant at their means (Supplemental Table 1, M1). The models of earnings show the unintended consequences of only well-paid leaves for mothers for both groups (Supplemental Table 2, M3). Increasing well-paid leaves for mothers results in increased gender wage gaps for both low- and highly educated women (y=-.18 percentiles and p <.05, low-educated; y=-.15 percentiles and p <.10, highly educated). The results suggest that only well-paid leave periods may have adverse consequences for the earnings of low- and highly educated women (compared to low- and highly educated men), supporting earlier findings by Mandel (2012).

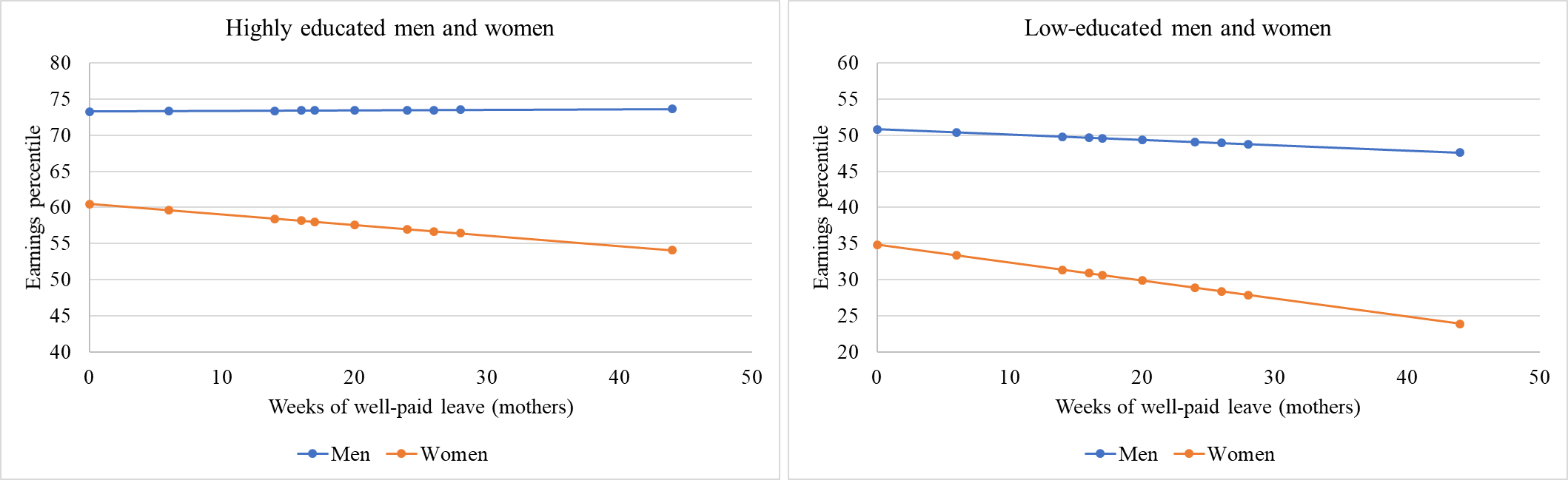

Figure 1. Predicted earnings percentiles by weeks of well-paid leaves (mothers)

Source: Predicted values were derived from Supplemental Table 2, Model 3 (for both low- and high educated men and women).

Figure constructed in Microsoft Excel.

Finally, Figure 1 shows the predicted earnings percentiles of both low-and highly educated men and women at the different lengths of well-paid leaves for mothers (ranging from a low of 0 weeks to a high of 44 weeks). The predicted earnings of low- and highly educated men remains largely the same, regardless of the length of well-paid leave for mothers. However, the predicted earnings of low- and highly educated women decline the longer the weeks of well-paid leave for mothers. Therefore, gender earnings gaps between low-educated men and women and highly educated men and women are wider the longer the length of well-paid leave.

Conclusions

First, this short article highlights the importance of constructing and using more precise, disaggregated, and multidimensional measures in work-family policy research. Correlations among the policy dimensions showed the importance of measuring leave policy at different wage cutoffs. Leave policies that are generous in terms of length and payment are not the same policies that are generous in terms of length but not payment. The results suggest singular policy measures used in many past studies may not represent the scope of leave policy more generally. For ECEC, though I constructed two measures of generosity using enrollment rates (like past studies), other dimensions – such as opening hours – continue to be difficult to measure due to data limitations and regulations about how ECEC is set up across high-income countries (Hook and Li 2020; Kostecki 2021; Sirén et al. 2020).

Regarding relationships specifically between leave policies and outcomes, I argue what matters is how different leave policy dimensions drive unintended consequences for women in employment and others not at all. Well-paid leaves for mothers may adversely affect the earnings of women, by class, more than unpaid/poorly paid leaves for mothers. More consideration needs to be given to fathers’ leave and relationships with women’s employment and attainment, by class. Also important is to address the issues of unintended consequences of leave policies for women/mothers of different class groups and to evaluate the link between gender employment inequalities and other policies such as working time regulations.8

There is a growing consensus that ECEC is not adversely linked with women’s employment or attainment, relative to men (Brady, Blome, and Kmec 2020; Hook and Li 2020; Mandel 2012; Olivetti and Petrongolo 2017). My findings support past research. To study leave and ECEC together, research questions need to be reframed around the specific effects we expect to see of both policies – positive and negative.

No leave policy across the 24 countries provides working mothers and fathers with equal amounts of reserved, nontransferable well-paid leaves (Table 1). Overall, I argue leave policies that treat men and women the same and promote equality in the gendered division of labor can at the very least promote gender equality in employment. However, the understanding that gender employment inequalities may occur because of certain design features of leave policy can help policy makers to continually improve this policy over time to adapt to the needs of working parents.

1For some exceptions, see Korpi, Ferrarini, and Englund (2013) and Olivetti and Petrongolo (2017).

2See specifically chapter 3 in my dissertation for past studies that have considered the development and measurement of leave and ECEC policy across different dimensions and relationships to women’s employment. I drew on these studies to develop the indicators in my research.

3Chapter 3 in my dissertation also shows different relationships among the leave and ECEC policy measures used in three studies – Mandel and Semyonov (2005, 2006) and Brady, Blome, and Kmec (2020). In Mandel and Semyonov (2005, 2006), fully paid maternity leave is positively and significantly correlated with enrollment rates of children 0-6 years of age in publicly subsidized childcare (policies used to construct the Welfare State Intervention Index (WSII)). However, in Brady, Blome, and Kmec (2020), the measure of weeks of paid leave is not correlated with the percentage of children 0-6 enrolled in publicly subsidized childcare. Should we expect to see positive relationships among policy indicators?

4LIS follows the ISCED 2011 standard measure of classification to ensure education is comparable across countries.

5As gender differences might be less pronounced on net or mixed datasets than in gross datasets, assuming progressive taxation.

6The LIS database reports three possible current incomes—gross, mixed, and net. For the 24 high-income countries included in this study, the LIS data for France 2010 and Poland 2013 report mixed income—total individual annual earnings do not account for full taxes and contributions. The LIS data for Hungary 2012 and Slovenia 2012 reports net income—total annual earnings does not capture taxes and contributions. These four countries are excluded from the earnings correlations and models. The additional 20 datasets report gross income (taxes and contributions are fully captured, collect, or imputed). In addition, Denmark 2013, France 2010, Norway 2013, Poland 2013, and Slovenia 2012 do not report weekly working hours. Weekly working hours is an important factor to evaluating gender earnings gaps. However, Mandel (2012) utilizes a control of weekly hours worked in her earnings models while Brady, Blome, and Kmec (2020) do not. Summarizing Misra et al. (2011), Brady, Blome, and Kmec (2020) argue “Annual earnings combine pay and quantity of hours, both of which are relevant to evaluating work–family policies.” My decision was to include weekly hours worked because in my work with original household income surveys, there is no indication that annual earnings combine information about pay and quantity of hours (though more hours worked generally means higher annual earnings). Hours worked is therefore a necessary control to include in the models. In a future study, hours worked could be excluded as a control (and the countries that do not report weekly hours worked can be re-introduced) to determine how the results change. Countries that report net or mixed income data could also be included to determine how the results change.

7Before annual earnings were converted to country specific percentiles, negative earnings were bottom coded by converting them to 0. At the top of the distribution, annual earnings were top coded at 10 times above the median. By utilizing country specific percentiles Mandel (2012, 245–246) argues this method is used to “avoid conflating the effect of welfare state policies with the effect of wage-setting institutions. Each respondent’s wage is measured by his or her position in their national earnings distribution, irrespective of cross-national differences in the length of the wage ladder.”

8My dissertation research addresses the question of class tradeoffs among women and finds that class employment gaps between low- and highly educated women may be exacerbated by some design features of leave policy

References

| Brady, D.; Blome, A.; Kmec, J. A. (2020). “Work–Family Reconciliation Policies and Women’s and Mothers’ Labor Market Outcomes in Rich Democracies”, Socio-Economic Review, 18 (1): 125–61, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy045. |

| Hook, J. L. and Li, M. (2020). “Gendered Tradeoffs”, in The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy, edited by Nieuwenhuis, R. and Van Lancker, W., Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 249–66, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_11. |

| Korpi, W.; Ferrarini, T; Englund, S. (2013). “Women’s Opportunities under Different Family Policy Constellations: Gender, Class, and Inequality Tradeoffs in Western Countries Re-Examined”, Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20 (1): 1–40, https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs028. |

| Gornick, Janet C. and Meyers, M. K. (2009). Gender Equality: Transforming Family Divisions of Labor. Vol. VI. The Real Utopias Project. New York, NY: Verso. |

| Kostecki, S. L. (2021). “Work-Family Reconciliation Policies Reexamined: Good or Bad for Gender and Class Inequality in Employment across Twenty-Four High-Income Countries?”, CUNY Academic Works, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4304. |

| Misra, J., Budig, M. J., and Boeckmann, I. (2011). “Cross-National Patterns in Individual and Household Employment and Work Hours by Gender and Parenthood”, Comparing European Workers Part A, Research in the Sociology of Work, 22, 169–207. |

| Mandel, H. (2012). “Winners and Losers: The Consequences of Welfare State Policies for Gender Wage Inequality”, European Sociological Review, 28 (2): 241–62, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq061. |

| Mandel, H. and Semyonov, M. (2005). “Family Policy, Wage Structures, and Gender Gaps: Sources of Earnings Inequality in 20 Countries”, American Sociological Review, 70 (December): 949–67. |

| Mandel, H. and Semyonov, M. (2006). “A Welfare State Paradox: State Interventions and Women’s Employment Opportunities in 22 Countries”, American Journal of Sociology, 111 (6): 1910–49. |

| Olivetti, C. and Petrongolo, B. (2017). “The Economic Consequences of Family Policies: Lessons from a Century of Legislation in High-Income Countries”, IZA Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper 10505, January. |

| Pettit, B. and Hook, J. L. (2009). Gendered Tradeoffs: Family, Social Policy, and Economic Inequality in Twenty-One Countries. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. |

| Sirén, S.; Doctrinal, L.; Van Lancker, W.; Nieuwenhuis, R. (2020). “Childcare Indicators for the Next Generation of Research”, in The Palgrave Handbook of Family Policy, edited by Nieuwenhuis, R. and Van Lancker, W., Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 627–55, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-54618-2_24. |

| ***See full bibliographic information for policy indicators in the Leave and ECEC policy dimensions dataset documentation. |